Graal Truffle tutorial part 9 – performance benchmarking

This article is part of a tutorial on GraalVM's Truffle language implementation framework.

- Part 0 – what is Truffle

- Part 1 – setup, Nodes, CallTarget

- Part 2 – introduction to specializations

- Part 3 – specializations with Truffle DSL, TypeSystem

- Part 4 – parsing, and the TruffleLanguage class

- Part 5 – global variables

- Part 6 – static function calls

- Part 7 – function definitions

- Part 8 – conditionals, loops, control flow

- Part 9 – performance benchmarking

- Part 10 – arrays, read-only properties

- Part 11 – strings, static method calls

- Part 12 – classes 1: methods, new

- Part 13 – classes 2: fields, this, constructors

- Part 14 – classes 3: inheritance, super

- Part 15 – exceptions

- Part 16 – debuggers

In many previous articles in this series, I used the argument of performance to justify why some code was written in a particular way. However, since we never actually measured and compared the performance of our interpreter, you had to take my word for it that the code we wrote was indeed “fast”.

In this article, we will change that, and finally explore the performance of our interpreter. First, we’ll write some benchmarks, compare the numbers, and then see how can we improve them. In the process, we will see how to diagnose performance issues using the Ideal Graph Visualizer (IGV) tool.

Measured code

As our benchmark, we will use the classic, “naive” implementation of the function calculating the Fibonacci sequence. Here it is in JavaScript:

function fib(n) {

if (n < 2) {

return 1;

}

return fib(n - 1) + fib(n - 2);

}

While this is obviously not the most efficient way of implementing this function,

it’s a popular benchmark nonetheless, as it stress-tests the performance of function calls,

which are one of the most critical parts of a performant language implementation.

Our benchmark will call this function to calculate the twentieth Fibonacci number,

so fib(20).

There’s one small wrinkle we need to handle first: this program uses the subtraction operation, which we don’t support in EasyScript yet. Let’s start by adding it.

Supporting subtraction in EasyScript

Support for subtraction is quite easy to add, as this operation is very similar to addition.

First, we need a small change to our ANTLR grammar:

expr4 : left=expr4 o=('+' | '-') right=expr5 #AddSubtractExpr4

...

Instead of a production that only handles addition,

we add support for subtraction by allowing the operator to be either +, or -.

We use the new class in our parser:

public final class EasyScriptTruffleParser {

// ...

private EasyScriptExprNode parseAdditionSubtractionExpr(EasyScriptParser.AddSubtractExpr4Context addSubtractExpr) {

EasyScriptExprNode leftSide = this.parseExpr4(addSubtractExpr.left);

EasyScriptExprNode rightSide = this.parseExpr5(addSubtractExpr.right);

switch (addSubtractExpr.o.getText()) {

case "+":

return AdditionExprNodeGen.create(leftSide, rightSide);

case "-":

default:

return SubtractionExprNodeGen.create(leftSide, rightSide);

}

}

}

And the subtraction Node itself is pretty much identical to the addition one:

import com.oracle.truffle.api.dsl.Fallback;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.dsl.Specialization;

public abstract class SubtractionExprNode extends BinaryOperationExprNode {

@Specialization(rewriteOn = ArithmeticException.class)

protected int subtractInts(int leftValue, int rightValue) {

return Math.subtractExact(leftValue, rightValue);

}

@Specialization(replaces = "subtractInts")

protected double subtractDoubles(double leftValue, double rightValue) {

return leftValue - rightValue;

}

/** Non-numbers cannot be subtracted, and always result in NaN. */

@Fallback

protected double subtractNonNumber(Object leftValue, Object rightValue) {

return Double.NaN;

}

}

The benchmark structure

When talking about benchmarking on the JVM, one name should come to mind immediately: the JMH library. It’s the gold standard for measuring performance of code running on the JVM, which is very tricky to do reliably, because of the Just-in-Time compilation that happens during runtime, not compile time.

JMH has a ton of options that you can set for your benchmark – check out the library’s examples for details. Because of that, I like to introduce a common benchmark superclass that gathers the shared configuration:

import org.graalvm.polyglot.Context;

import org.openjdk.jmh.annotations.BenchmarkMode;

import org.openjdk.jmh.annotations.Fork;

import org.openjdk.jmh.annotations.Measurement;

import org.openjdk.jmh.annotations.Mode;

import org.openjdk.jmh.annotations.OutputTimeUnit;

import org.openjdk.jmh.annotations.Scope;

import org.openjdk.jmh.annotations.Setup;

import org.openjdk.jmh.annotations.State;

import org.openjdk.jmh.annotations.TearDown;

import org.openjdk.jmh.annotations.Warmup;

import java.util.concurrent.TimeUnit;

@Warmup(iterations = 5, time = 1)

@Measurement(iterations = 5, time = 1)

@Fork(value = 1, jvmArgsAppend = "-Dgraalvm.locatorDisabled=true")

@BenchmarkMode(Mode.AverageTime)

@OutputTimeUnit(TimeUnit.MICROSECONDS)

@State(Scope.Benchmark)

public abstract class TruffleBenchmark {

protected Context truffleContext;

@Setup

public void setup() {

this.truffleContext = Context.create();

}

@TearDown

public void tearDown() {

this.truffleContext.close();

}

}

We set both the warmup and the actual measurement to 5 iterations, 1 second each.

That should be more than enough to make sure the JIT compilation is triggered consistently.

We make sure we pass the -Dgraalvm.locatorDisabled=true

option to the forked JVM that the benchmark executes in,

so that our custom Truffle language implementation is registered by the GraalVM runtime.

I like to use average operation time as the measurement methodology, probably because I’m accustomed to tracking service invocation latency in that same way. Feel free to use throughput, that is the number of operations per unit of time, usually second, if that’s what you prefer. We’ll use microseconds as our unit, which in my experience is a good compromise between getting huge numbers that are difficult to read at a glance with nanoseconds, and getting too similar numbers with milliseconds.

Finally, we create a GraalVM polyglot Context for each benchmark,

which we will use for running our interpreters

(hence why the field is protected),

in the lifecycle @Setup and @TearDown methods,

which are very similar to methods with the same annotations from test frameworks like JUnit.

The benchmark

The benchmark class extends our above superclass:

import org.openjdk.jmh.annotations.Benchmark;

public class FibonacciBenchmark extends TruffleBenchmark {

private static final String FIBONACCI_JS_FUNCTION = "" +

"function fib(n) { " +

" if (n < 2) { " +

" return 1; " +

" } " +

" return fib(n - 1) + fib(n - 2); " +

"}";

private static final String FIBONACCI_JS_PROGRAM = FIBONACCI_JS_FUNCTION + "fib(20);";

@Benchmark

public int recursive_eval_ezs() {

return this.truffleContext.eval("ezs", FIBONACCI_JS_PROGRAM).asInt();

}

// ...

}

Benchmark methods are annotated with @Benchmark.

The JMH harness will call it repeatedly, measuring its average performance over thousands of samples,

making sure it was JIT-compiled first.

It’s important to return a value from benchmark methods,

as otherwise there’s a risk the Java optimizer will completely discard the benchmarked code,

because it might figure out that the value produced is never actually used,

in which case we would measure a no-op method!

You might be worried that we’re calling Context.eval() repeatedly like this,

because the code needs to be parsed first into the Truffle AST, which would surely affect its performance.

However, it turns out that it’s not an issue,

as the GraalVM polyglot support has built-in caching,

so this code will only be parsed the first time it’s executed,

and then the existing Truffle AST nodes will be re-used on subsequent eval()s.

For simplicity, we are re-evaluating the entire program,

including the function definition,

on each iteration of the benchmark.

That might introduce some overhead,

so, for your benchmarks, you might consider splitting the definition from the invocation.

You can take out a function as a GraalVM polyglot Value

from the language’s global bindings,

like we did in part 5,

and use the Value.execute() method

to invoke it,

or pass just the invocation code

(so, fib(20) in our case)

to Context.eval(),

perhaps using the Source class.

So, that method covers our EasyScript interpreter measurements; however, when benchmarking, it’s always important not to rely solely on absolute numbers, but to track performance relative to other similar code.

The obvious baseline is implementing the same Fibonacci function in Java:

import org.openjdk.jmh.annotations.Benchmark;

public class FibonacciBenchmark extends TruffleBenchmark {

// ...

public static int fibonacciRecursive(int n) {

return n < 2

? 1

: fibonacciRecursive(n - 1) + fibonacciRecursive(n - 2);

}

@Benchmark

public int recursive_java() {

return fibonacciRecursive(20);

}

// ...

}

Another good candidate for a comparative benchmark is using the

GraalVM JavaScript implementation.

This interpreter used to be bundled inside GraalVM,

but starting with version 22,

it is now distributed separately,

so we need to add a dependency to our project on the

JAR containing it:

dependencies {

// ...

implementation "org.graalvm.js:js:22.3.0"

}

// ...

And with that, we can execute the same benchmark program, but with JavaScript instead of EasyScript:

import org.openjdk.jmh.annotations.Benchmark;

public class FibonacciBenchmark extends TruffleBenchmark {

// ...

@Benchmark

public int recursive_js_eval() {

return this.truffleContext.eval("js", FIBONACCI_JS_PROGRAM).asInt();

}

// ...

}

And finally, we also introduce one more Truffle language for comparison: SimpleLanguage. It’s an educational language implementation that is maintained by the Truffle team, and its purpose is to be the entrypoint for developers to learn Truffle. In my opinion, it’s quite difficult to read without knowing a lot about Truffle already (in fact, there are elements of the SimpleLanguage codebase that I still don’t understand even now!). However, it’s really helpful when used as a performance reference, as, even though it’s an educational implementation, it has a strong focus on performance.

To use SimpleLanguage,

similarly like for JavaScript,

we need to add a dependency to our project in the build.gradle file:

dependencies {

// ...

implementation "org.graalvm.truffle:truffle-sl:22.3.0"

}

// ...

And then we can write a benchmark for it:

import org.openjdk.jmh.annotations.Benchmark;

public class FibonacciBenchmark extends TruffleBenchmark {

// ...

@Benchmark

public int recursive_sl_eval() {

return this.truffleContext.eval("sl", FIBONACCI_JS_FUNCTION +

"function main() { " +

" return fib(20); " +

"}").asInt();

}

}

SimpleLanguage is very similar to JavaScript,

but doesn’t allow statements on the global level, only function definitions,

and the main function is the entrypoint

(similar to how Java does it),

so we need to modify the benchmarked program slightly.

Initial results

When running the jmh Gradle target with the code of EasyScript from the

previous article,

on my laptop, I get the following results:

Benchmark Mode Cnt Score Error Units

FibonacciBenchmark.recursive_eval_ezs avgt 5 6028.256 ± 421.844 us/op

FibonacciBenchmark.recursive_eval_js avgt 5 78.143 ± 3.453 us/op

FibonacciBenchmark.recursive_eval_sl avgt 5 55.662 ± 3.395 us/op

FibonacciBenchmark.recursive_java avgt 5 38.383 ± 1.046 us/op

This is fascinating – our EasyScript interpreter is almost 200 times slower than Java! But clearly, this is not something intrinsic to Truffle, because the GraalVM JavaScript implementation is very fast – only twice as slow as the Java version. More amazingly, SimpleLanguage is even faster than JavaScript, being only 1.5 times slower than Java, and that small difference can probably be attributed to the GraalVM polyglot API overhead (and to the fact that Java is a statically-typed language, while SimpleLanguage is dynamically-typed, like JavaScript).

Given the results, we clearly have some work to do in order to move EasyScript closer to SimpleLanguage and the GraalVM JavaScript implementation performance.

Simple changes

In some cases, you can discover a source for slowness by doing comparison experiments.

For example, in the code of the benchmark, the if statement uses a block:

if (n < 2) {

return 1;

}

However, if we instead use a single statement instead of a block:

if (n < 2)

return 1;

suddenly we get a 3x speedup in our benchmark:

Benchmark Mode Cnt Score Error Units

FibonacciBenchmark.recursive_eval_ezs avgt 5 2135.922 ± 144.021 us/op

This is very surprising, as we don’t expect to see any difference in performance between the two programs!

If we look at the implementation of the node that represents a block of statements,

BlockStmtNode:

import com.oracle.truffle.api.frame.VirtualFrame;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.nodes.ExplodeLoop;

public final class BlockStmtNode extends EasyScriptStmtNode {

@Children

private final EasyScriptStmtNode[] stmts;

public BlockStmtNode(List<EasyScriptStmtNode> stmts) {

this.stmts = stmts.toArray(new EasyScriptStmtNode[]{});

}

@Override

@ExplodeLoop

public Object executeStatement(VirtualFrame frame) {

Object ret = Undefined.INSTANCE;

for (EasyScriptStmtNode stmt : this.stmts) {

ret = stmt.executeStatement(frame);

}

return ret;

}

}

The implementation is simple, but there’s one thing that stands out to me as a potential inefficiency: we do many redundant assignments, while only the last assignment in the loop has any effect. Could it be possible that the Graal optimizer can’t figure that out, and generates sub-optimal code in this case?

If we change the implementation to be a little more complicated, but don’t perform redundant assignments:

import com.oracle.truffle.api.frame.VirtualFrame;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.nodes.ExplodeLoop;

public final class BlockStmtNode extends EasyScriptStmtNode {

// ...

@Override

@ExplodeLoop

public Object executeStatement(VirtualFrame frame) {

int stmtsMinusOne = this.stmts.length - 1;

for (int i = 0; i < stmtsMinusOne; i++) {

this.stmts[i].executeStatement(frame);

}

return stmtsMinusOne < 0 ? Undefined.INSTANCE : this.stmts[stmtsMinusOne].executeStatement(frame);

}

}

We get the same performance for the block program as for the program without the block:

FibonacciBenchmark.recursive_eval_ezs avgt 5 2163.692 ± 82.852 us/op

So, it seems like our above hypothesis about Graal generating sub-optimal code was indeed correct, as a simple refactoring resulted in a 3x speedup!

Using Ideal Graph Visualizer

While that was a great win, it’s not always easy to formulate experiments that keep the semantics of the code the same – for example, how would you create an experiment that checks whether function calls are slow? In those more complicated cases, the Ideal Graph Visualizer tool is helpful.

It’s a project maintained by the same team that maintains GraalVM and Truffle, and allows visualizing as graphs the many debug trees that Truffle and Graal produce in the process of interpreting your language.

To have your Truffle interpreter emit graphs to consume in IGV,

you need to add the -Dgraal.Dump=:1 JVM argument when starting it.

You can send the dumps directly to the program with the

-Dgraal.PrintGraph=Network, or to a specific file by passing the -Dgraal.DumpPath argument

(the default is to save them in the graal_dumps

folder in the current directory if they cannot be delivered to a running instance of IGV).

For example, to dump the data from the EasyScript benchmark, you can add the appropriate JVM arguments in the benchmark configuration:

import org.openjdk.jmh.annotations.Benchmark;

import org.openjdk.jmh.annotations.Fork;

public class FibonacciBenchmark extends TruffleBenchmark {

// ...

@Fork(jvmArgsPrepend = {

"-Dgraal.Dump=:1",

"-Dgraal.PrintGraph=Network"

})

@Benchmark

public int recursive_eval_ezs() {

return this.truffleContext.eval("ezs", FIBONACCI_JS_PROGRAM).asInt();

}

}

After downloading IGV,

run it by executing ./idealgraphvisualizer

in the bin directory of the downloaded and uncompressed program.

Now, when running the benchmark, you should see in the output:

[Use -Dgraal.LogFile=<path> to redirect Graal log output to a file.]

Connected to the IGV on 127.0.0.1:4445

And a bunch of entries should appear in the “Outline” menu on the left.

Each of those entries represents a GraalVM graph.

Now, there are many graphs, but the ones that interest us today start with TruffleAST.

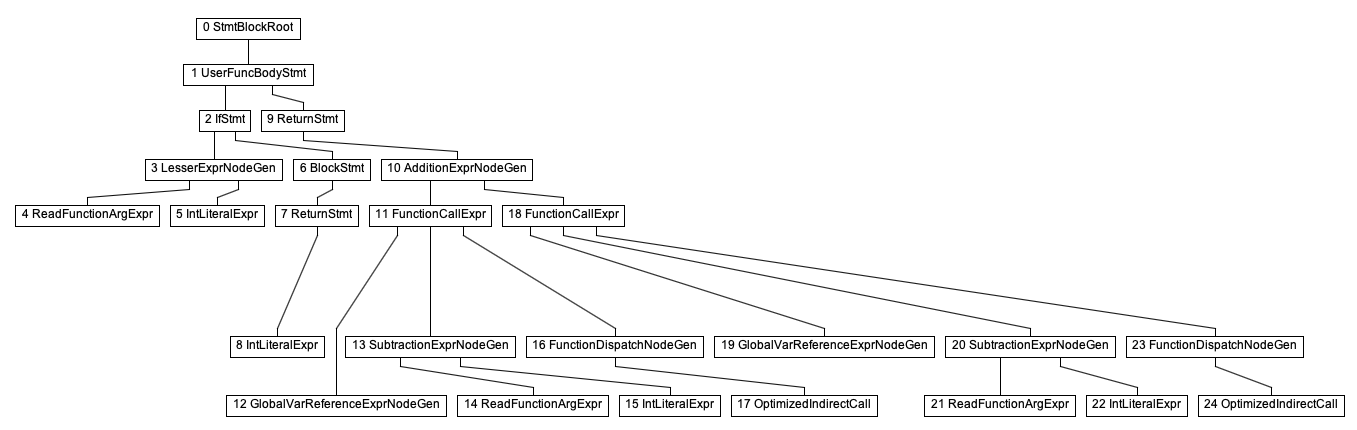

If we click on one of them generated by the EasyScript benchmark,

we’ll see something like this:

This is the Truffle AST for our fib function!

You can click on any of nodes in the graph,

and you’ll see the values it contains – for example,

clicking on node number 5, IntLiteralExprNode

(the “Node” suffix gets removed by IGV from the labels in the graph,

as it’s implied that all vertexes in the graphs represents Truffle nodes),

you’ll see that it has value 2,

which makes perfect sense, because that part of the graph corresponds to the code:

if (n < 2) { //...

The thing that stands out to me in this graph are the nodes with numbers 17 and 24.

They represent recursive invocations of the fib function in the expression

fib(n - 1) + fib(n - 2).

The worrying part is that they are OptimizedIndirectCallNodes –

but since we’re simply calling fib in both cases,

we would expect these to be direct call nodes, not indirect ones!

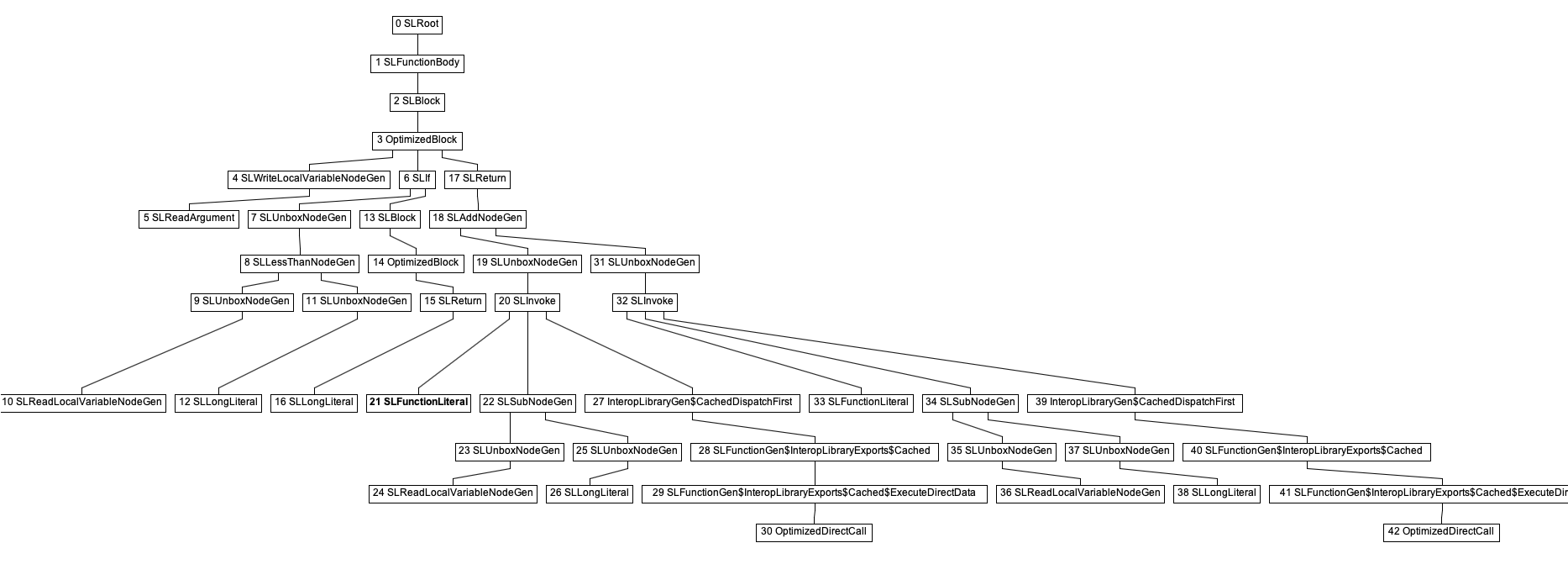

If we compare that to the graph for the fib function generated by SimpleLanguage:

The general shape of the graph is identical

(although SimpleLanguage adds a few more nodes at each level),

but we can clearly see that the recursive calls to fib

(nodes number 30 and 42)

are OptimizedDirectCalls.

This explains why the SimpleLanguage implementation is so much faster than our EasyScript one.

Adding caching

The problem should be clear when we think through how our code from part 8 behaves when we execute the same Truffle AST multiple times (remember, the Truffle AST gets cached when the same program is evaluated more than once):

- In the function declaration node for

fib, we create a newCallTarget. - We save that

CallTargetwrapped in a newFunctionObject, in the global variables map. - In the function dispatch node, we notice that the

CallTargetwas changed, and so we can’t use the direct call path, and must settle for the indirect one.

To fix this, we need to add some caching to our Nodes, in order to stop performing redundant work.

If we look at the code of SimpleLanguage,

we see that its equivalent of our FunctionObject,

the SLFunction class,

is actually mutable –

it has a method called setCallTarget()

which changes the CallTarget a given function points to.

If we made FunctionObject mutable too,

we could suddenly cache it in our nodes that define and reference it,

and we would avoid searching for it each time in our global variables Map!

Let’s make FunctionObject mutable:

import com.oracle.truffle.api.Assumption;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.CallTarget;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.interop.TruffleObject;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.utilities.CyclicAssumption;

public final class FunctionObject implements TruffleObject {

private final String functionName;

private final CyclicAssumption functionWasNotRedefinedCyclicAssumption;

private final FunctionDispatchNode functionDispatchNode;

private CallTarget callTarget;

private int argumentCount;

public FunctionObject(String functionName, CallTarget callTarget, int argumentCount) {

this.functionName = functionName;

this.functionWasNotRedefinedCyclicAssumption = new CyclicAssumption(this.functionName);

this.functionDispatchNode = FunctionDispatchNodeGen.create();

this.callTarget = callTarget;

this.argumentCount = argumentCount;

}

public void redefine(CallTarget callTarget, int argumentCount) {

if (this.callTarget != callTarget) {

this.callTarget = callTarget;

this.argumentCount = argumentCount;

this.functionWasNotRedefinedCyclicAssumption.invalidate("Function '" + this.functionName + "' was redefined");

}

}

public Assumption getFunctionWasNotRedefinedAssumption() {

return this.functionWasNotRedefinedCyclicAssumption.getAssumption();

}

public CallTarget getCallTarget() {

return this.callTarget;

}

public int getArgumentCount() {

return this.argumentCount;

}

// ...

}

The callTarget and argumentCount fields are no longer final,

but now can be re-set with the redefine() method.

We keep an Assumption that allows checking whether a function was redefined.

An Assumption is a special class that the Graal compiler knows about which allows gating some optimizations behind a condition.

An Assumption starts as true, and then you can invalidate it;

once it has been invalidated, it can never be true again.

A CyclicAssumption is a commonly-used utility class that creates a new Assumption

each time the previous one has been invalidated.

With a mutable FunctionObject,

we can now change the API of the GlobalScopeObject that stores them.

Instead of taking in a FunctionObject as an argument,

we will now take in a CallTarget, and the argument count as an int,

and we will call redefine() on the FunctionObject if we already have a function with that name

(remember, in JavaScript, it’s legal to define a function with a name that already exists):

import com.oracle.truffle.api.CallTarget;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.interop.InteropLibrary;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.interop.TruffleObject;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.library.ExportLibrary;

@ExportLibrary(InteropLibrary.class)

public final class GlobalScopeObject implements TruffleObject {

private final Map<String, Object> variables = new HashMap<>();

private final Set<String> constants = new HashSet<>();

public FunctionObject registerFunction(String funcName, CallTarget callTarget, int argumentCount) {

// we allow overwriting functions, but we add them to the constants set,

// so that they can't be changed to a non-function value with assignment

// (as that would break the caching assumption in GlobalVarReferenceExprNode)

this.constants.add(funcName);

Object existingVariable = this.variables.get(funcName);

// instanceof returns 'false' for null,

// so this also covers the case when we're seeing this variable for the first time

if (existingVariable instanceof FunctionObject) {

FunctionObject existingFunction = (FunctionObject) existingVariable;

existingFunction.redefine(callTarget, argumentCount);

return existingFunction;

} else {

FunctionObject newFunction = new FunctionObject(funcName, callTarget, argumentCount);

this.variables.put(funcName, newFunction);

return newFunction;

}

}

// ...

}

With this, we can change the implementation of function declaration:

import com.oracle.truffle.api.CallTarget;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.CompilerDirectives;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.CompilerDirectives.CompilationFinal;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.frame.FrameDescriptor;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.frame.VirtualFrame;

public final class FuncDeclStmtNode extends EasyScriptStmtNode {

private final String funcName;

private final FrameDescriptor frameDescriptor;

private final int argumentCount;

@SuppressWarnings("FieldMayBeFinal")

@Child

private UserFuncBodyStmtNode funcBody;

@CompilationFinal

private CallTarget cachedCallTarget;

@CompilationFinal

private FunctionObject cachedFunction;

public FuncDeclStmtNode(String funcName, FrameDescriptor frameDescriptor, UserFuncBodyStmtNode funcBody, int argumentCount) {

this.funcName = funcName;

this.frameDescriptor = frameDescriptor;

this.funcBody = funcBody;

this.argumentCount = argumentCount;

this.cachedCallTarget = null;

this.cachedFunction = null;

}

@Override

public Object executeStatement(VirtualFrame frame) {

if (this.cachedCallTarget == null) {

CompilerDirectives.transferToInterpreterAndInvalidate();

var truffleLanguage = this.currentTruffleLanguage();

var funcRootNode = new StmtBlockRootNode(truffleLanguage, this.frameDescriptor, this.funcBody);

this.cachedCallTarget = funcRootNode.getCallTarget();

var context = this.currentLanguageContext();

this.cachedFunction = context.globalScopeObject.registerFunction(this.funcName, this.cachedCallTarget, this.argumentCount);

}

this.cachedFunction.redefine(this.cachedCallTarget, this.argumentCount);

return Undefined.INSTANCE;

}

}

We cache both the CallTarget that we create

(because there’s no point in creating a new one each time –

they would have the same behavior anyway),

and also the FunctionObject –

this way, we won’t have to search for it in the Map of global variables,

which is code the Graal optimizer might have trouble making fast.

Same as in part 2,

we need to make sure to annotate the cached fields with @CompilationFinal,

and also call CompilerDirectives.transferToInterpreterAndInvalidate()

when writing them, in case the code was JIT-compiled before it was first executed.

Also, now that we always return the same FunctionObject

instance for a given name, we can add caching to the variable reference Node:

import com.oracle.truffle.api.CompilerDirectives;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.CompilerDirectives.CompilationFinal;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.dsl.NodeField;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.dsl.Specialization;

@NodeField(name = "name", type = String.class)

public abstract class GlobalVarReferenceExprNode extends EasyScriptExprNode {

protected abstract String getName();

@CompilationFinal

private FunctionObject cachedFunction = null;

@Specialization

protected Object readVariable() {

if (this.cachedFunction != null) {

return this.cachedFunction;

}

String variableId = this.getName();

var context = this.currentLanguageContext();

var value = context.globalScopeObject.getVariable(variableId);

if (value == null) {

throw new EasyScriptException(this, "'" + variableId + "' is not defined");

}

if (value instanceof FunctionObject) {

CompilerDirectives.transferToInterpreterAndInvalidate();

this.cachedFunction = (FunctionObject) value;

}

return value;

}

}

This way, references like fib will be very fast in compiled code.

And finally, we also need to update the function dispatch code,

to check that the Assumption about the function not being redefined is still true.

Fortunately, the @Specialization annotation has an assumptions

attribute that can be used for this purpose:

import com.oracle.truffle.api.Assumption;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.dsl.Cached;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.dsl.Specialization;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.nodes.DirectCallNode;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.nodes.Node;

public abstract class FunctionDispatchNode extends Node {

@Specialization(

guards = "function.getCallTarget() == directCallNode.getCallTarget()",

limit = "2",

assumptions = "functionWasNotRedefined"

)

protected static Object dispatchDirectly(

FunctionObject function, Object[] arguments,

@Cached("function.getFunctionWasNotRedefinedAssumption()") Assumption functionWasNotRedefined,

@Cached("create(function.getCallTarget())") DirectCallNode directCallNode) {

return directCallNode.call(extendArguments(arguments, function));

}

// ...

}

Results after changes

What are the effects of these changes? If we re-run the benchmark, we get the following results:

Benchmark Mode Cnt Score Error Units

FibonacciBenchmark.recursive_eval_ezs avgt 5 102.190 ± 1.099 us/op

So, we went from 6 000 microseconds per invocation to 100, with just a few minor code changes!

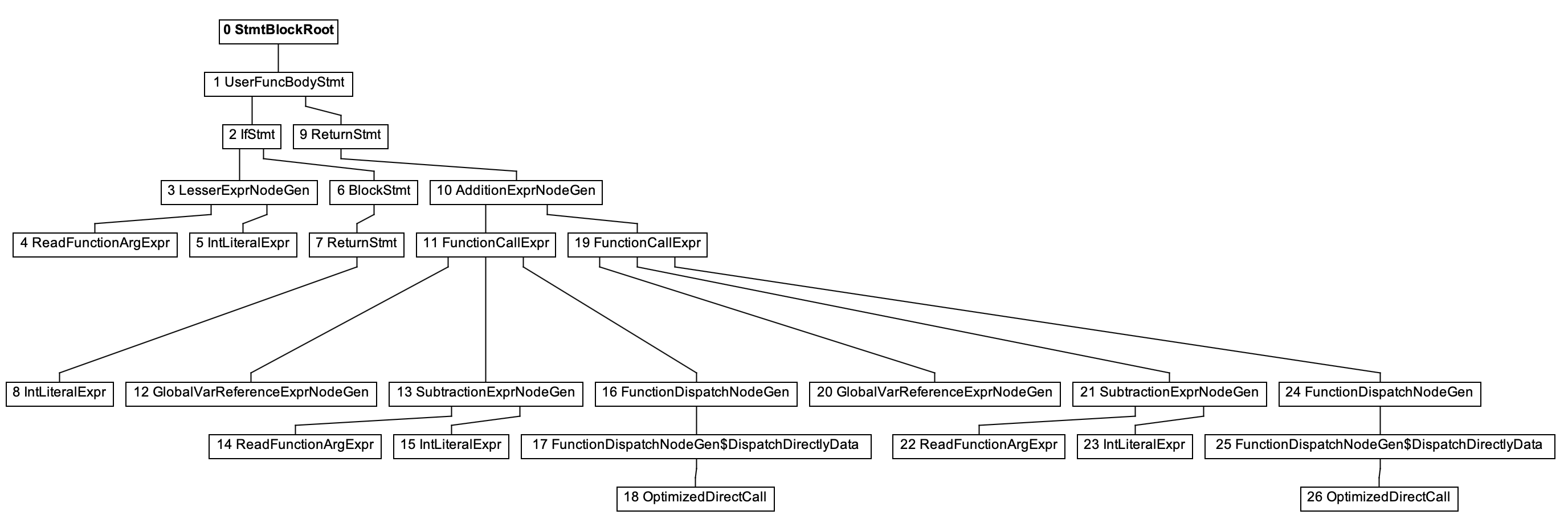

If we check the graph produced by the recursive_eval_ezs

benchmark now in Ideal Graph Visualizer, we’ll get:

As we can see, the leaves for recursive calls to the fib

function itself are now represented as OptimizedDirectCallNodes,

instead of the slow OptimizedIndirectCallNodes we had there before.

Summary

We achieved a 60x speedup of our interpreter with just a few minor changes to its code. I recommend always benchmarking your own interpreter in addition to writing unit tests for it, as otherwise it’s pretty difficult to predict how even minor changes will affect its performance – Graal, as most optimizing compilers, is so complex that it acts as basically a “black box” from the perspective of the language implementer, and can often surprise you.

As usual, all code from the article is available on GitHub.

We’ve barely scratched the surface of the capabilities of Ideal Graph Visualizer in this article – it’s a very powerful, if slightly tricky to use, tool. If you want to learn more about it, I recommend the following resources:

- “Understanding How Graal Works” by Chris Seaton

- “A friendlier visualization of Java JIT’s compiler control flow” by Roberto Castañeda Lozano

- “Visualization of Program Dependence Graphs”, the master thesis of Thomas Würthinger, the author of IGV

In the next part of the series, we will talk about implementing arrays, and adding properties (for now, just reading them – without writing) to our language.

This article is part of a tutorial on GraalVM's Truffle language implementation framework.

- Part 0 – what is Truffle

- Part 1 – setup, Nodes, CallTarget

- Part 2 – introduction to specializations

- Part 3 – specializations with Truffle DSL, TypeSystem

- Part 4 – parsing, and the TruffleLanguage class

- Part 5 – global variables

- Part 6 – static function calls

- Part 7 – function definitions

- Part 8 – conditionals, loops, control flow

- Part 9 – performance benchmarking

- Part 10 – arrays, read-only properties

- Part 11 – strings, static method calls

- Part 12 – classes 1: methods, new

- Part 13 – classes 2: fields, this, constructors

- Part 14 – classes 3: inheritance, super

- Part 15 – exceptions

- Part 16 – debuggers