Graal Truffle tutorial part 6 – static function calls

This article is part of a tutorial on GraalVM's Truffle language implementation framework.

- Part 0 – what is Truffle

- Part 1 – setup, Nodes, CallTarget

- Part 2 – introduction to specializations

- Part 3 – specializations with Truffle DSL, TypeSystem

- Part 4 – parsing, and the TruffleLanguage class

- Part 5 – global variables

- Part 6 – static function calls

- Part 7 – function definitions

- Part 8 – conditionals, loops, control flow

- Part 9 – performance benchmarking

- Part 10 – arrays, read-only properties

- Part 11 – strings, static method calls

- Part 12 – classes 1: methods, new

- Part 13 – classes 2: fields, this, constructors

- Part 14 – classes 3: inheritance, super

- Part 15 – exceptions

- Part 16 – debuggers

Now that EasyScript supports global variables, we have enough infrastructure in place to add support for function calls. You might be surprised – don’t we need function definitions first, in order to have a function to call? Fortunately, basically all programming languages come with a bunch of built-in functions that any program written in that language can use, and JavaScript is no different – here’s a list of the language’s built-in values, which includes many functions.

In the article, to illustrate all of the concepts involved,

we will implement two static functions from the global

Math object:

abs(n),

which calculates the absolute value

of a given number,

and pow(x, y),

which raises x to the power of y.

Hopefully, these two examples give you enough information to implement any sort of built-in function you want in your own language.

Note that Math is an object in JavaScript,

and our EasyScript implementation doesn’t implement that concept just yet.

For that reason, in this part of the series,

we won’t allow expression to reference Math by itself;

we will only allow referencing a property of it,

like Math.abs, or Math.pow.

In this article,

we will also, for the first time in the series,

use the frame argument that is passed to each of the execute*() methods –

so, if reading through the series,

you kept wondering what that thing was for,

read on to finally find out!

Grammar

We need to add a new expression type for function calls.

We also introduce compound references, like Math.abs.

Here’s the updated grammar for expressions –

the rest of the grammar is the same as in

part 5:

expr1 : ID '=' expr1 #AssignmentExpr1

| expr2 #PrecedenceTwoExpr1

;

expr2 : left=expr2 '+' right=expr3 #AddExpr2

| '-' expr3 #UnaryMinusExpr2 // new

| expr3 #PrecedenceThreeExpr2

;

expr3 : literal #LiteralExpr3

| ID #SimpleReferenceExpr3

| ID '.' ID #ComplexReferenceExpr3 // new

| expr3 '(' (expr1 (',' expr1)*)? ')' #CallExpr3 // new

| '(' expr1 ')' #PrecedenceOneExpr3

;

Note that we still only allow assignment to simple variables,

even though in JavaScript it’s legal to overwrite things like Math.abs.

However, that would require a lot of infrastructure like objects,

properties, anonymous functions, etc. that we don’t have in EasyScript yet,

so, for the same reason we don’t allow referencing just Math,

we also won’t allow redefining the built-in functions for now.

We also add a negation expression to our language,

so that we can test the Math.abs function with negative numbers.

It will be very simple though, and nothing we haven’t seen in the previous articles in the series,

so I won’t even bother showing its implementation.

As in the previous parts,

we introduce a class, EasyScriptTruffleParser,

that parses an EasyScript program by first invoking the classes generated from the above grammar by ANTLR,

and then translating the returned ANLTR parse tree into the Truffle AST.

When parsing complex references,

we simply concatenate each of its parts with a dot in the middle:

public final class EasyScriptTruffleParser {

// ...

private static EasyScriptExprNode parseExpr3(EasyScriptParser.Expr3Context expr3) {

if (expr3 instanceof EasyScriptParser.LiteralExpr3Context) {

return parseLiteralExpr((EasyScriptParser.LiteralExpr3Context) expr3);

} else if (expr3 instanceof EasyScriptParser.SimpleReferenceExpr3Context) {

return parseReference(((EasyScriptParser.SimpleReferenceExpr3Context) expr3).ID().getText());

} else if (expr3 instanceof EasyScriptParser.ComplexReferenceExpr3Context) {

// we concatenate complex references with '.' in between

var complexRef = (EasyScriptParser.ComplexReferenceExpr3Context) expr3;

return parseReference(complexRef.ID().stream()

.map(id -> id.getText())

.collect(Collectors.joining(".")));

} else if (expr3 instanceof EasyScriptParser.CallExpr3Context) {

return parseCallExpr((EasyScriptParser.CallExpr3Context) expr3);

} else {

return parseExpr1(((EasyScriptParser.PrecedenceOneExpr3Context) expr3).expr1());

}

}

private static GlobalVarReferenceExprNode parseReference(String variableId) {

return GlobalVarReferenceExprNodeGen.create(variableId);

}

private static FunctionCallExprNode parseCallExpr(EasyScriptParser.CallExpr3Context callExpr) {

return new FunctionCallExprNode(

parseExpr3(callExpr.expr3()),

callExpr.expr1().stream()

.map(EasyScriptTruffleParser::parseExpr1)

.collect(Collectors.toList()));

}

}

So, a complex reference like Math.abs will be treated as a global variable with the name "Math.abs".

We will use that fact later, when defining our built-in functions.

TypeSystem

Before we show the FunctionCallExprNode,

we need to make a small change to the TypeSystem

class that we’ve been using since

part 3.

We will be writing a few new expression Nodes in this part that implement their execute*() methods directly,

instead of relying on the Truffle DSL to generate them.

To reduce duplication,

we only want to implement the most general executeGeneric() method in each of them,

and then the remaining ones we want to inherit from the base EasyScriptExprNode.

All of them should follow the same pattern:

call executeGeneric(), and check the type of returned value –

if it’s of the correct type, return it,

otherwise throw UnexpectedResultException.

We can write all of that by hand,

but there’s a simpler way.

The @TypeSystem annotation takes an optional value attribute that’s an array of types (class instances).

That array represents the hierarchy of the primitive types of your language,

in order from the smallest to the largest

(you don’t have to include Object explicitly,

it’s implied all languages will have it).

In the case of EasyScript at this moment,

that’s int and double:

import com.oracle.truffle.api.dsl.ImplicitCast;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.dsl.TypeSystem;

@TypeSystem({

int.class,

double.class,

})

public abstract class EasyScriptTypeSystem {

@ImplicitCast

public static double castIntToDouble(int value) {

return value;

}

}

When we provide the value attribute,

the Truffle DSL will generate a class with static methods to convert values into each of the specified types,

or throw UnexpectedResultException if it’s not possible.

We can use those methods in our base EasyScriptExprNode

class to implement the non-generic execute*() methods:

import com.oracle.truffle.api.dsl.TypeSystemReference;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.frame.VirtualFrame;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.nodes.Node;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.nodes.UnexpectedResultException;

@TypeSystemReference(EasyScriptTypeSystem.class)

public abstract class EasyScriptExprNode extends Node {

public abstract Object executeGeneric(VirtualFrame frame);

public int executeInt(VirtualFrame frame) throws UnexpectedResultException {

return EasyScriptTypeSystemGen.expectInteger(this.executeGeneric(frame));

}

public double executeDouble(VirtualFrame frame) throws UnexpectedResultException {

return EasyScriptTypeSystemGen.expectDouble(this.executeGeneric(frame));

}

}

Of course, in cases where we can implement executeInt() or executeDouble()

more efficiently, like for literal expressions,

we will still override these methods in our Node subclasses,

same way as we do in previous parts of the series.

FunctionObject

So, what is actually a “function” in Truffle?

Well, they are represented by a concept we’ve seen since

part 1 – CallTargets!

While we’ve been using them only as the entrypoints to our programs,

CallTargets represent all jumps to start execution of a given piece of code,

and that’s exactly what functions are.

So, to represent a function in our EasyScript language,

we’ll introduce a class that wraps a given CallTarget:

import com.oracle.truffle.api.CallTarget;

public final class FunctionObject {

public final CallTarget callTarget;

public FunctionObject(CallTarget callTarget) {

this.callTarget = callTarget;

}

}

For now, it’s extremely simple, but we’ll add more functionality to it a little later in the article.

Call expression Node

So, how does our expression for calling a function look like?

It will be the most complex Node we’ve implemented yet.

It has one child for representing the function being invoked,

and a collection of children for each of the arguments the function is invoked with.

For example, for a call like Math.pow(3, 4 + 5),

Math.pow is the expression representing the function being invoked,

and 3 and 4 + 5 are the two expressions representing the arguments of the call.

In the executeGeneric() method of the call expression Node,

we evaluate each of the children,

using their executeGeneric() methods.

This results in a value for the target of the function,

and an array of values for their arguments,

all of type Object.

Next, we need to check whether the value we got from evaluating the target expression is really a function –

so, in our case, an instance of the FunctionObject class that we’ve seen above.

We could check that manually using something like the instanceof operator,

but function calls are actually one of the most interesting places for Graal to perform optimizations

(like inlining, turning virtual calls into static calls, etc.);

for that reason, we want to use specializations for function calls.

However, the Truffle DSL has a limitation –

you can’t use it to write specializations that take a collection of values as an argument

that are the result of evaluating a variable amount of child Nodes,

like the function call expression Node has.

Because of this, we’ll introduce one more level of indirection.

We’ll create a new node, called the FunctionDispatchNode,

that doesn’t have any children itself,

but that does use the Truffle DSL,

and we’ll delegate the actual function call to that Node after evaluating the subexpressions:

import com.oracle.truffle.api.frame.VirtualFrame;

public final class FunctionCallExprNode extends EasyScriptExprNode {

@SuppressWarnings("FieldMayBeFinal")

@Child

private EasyScriptExprNode targetFunction;

@Children

private final EasyScriptExprNode[] callArguments;

@SuppressWarnings("FieldMayBeFinal")

@Child

private FunctionDispatchNode dispatchNode;

public FunctionCallExprNode(EasyScriptExprNode targetFunction, List<EasyScriptExprNode> callArguments) {

this.targetFunction = targetFunction;

this.callArguments = callArguments.toArray(new EasyScriptExprNode[]{});

this.dispatchNode = FunctionDispatchNodeGen.create();

}

@Override

@ExplodeLoop

public Object executeGeneric(VirtualFrame frame) {

Object function = this.targetFunction.executeGeneric(frame);

Object[] argumentValues = new Object[this.callArguments.length];

for (int i = 0; i < this.callArguments.length; i++) {

argumentValues[i] = this.callArguments[i].executeGeneric(frame);

}

return this.dispatchNode.executeDispatch(function, argumentValues);

}

}

Notice we annotate the executeGeneric() method with the @ExplodeLoop annotation.

We’ve already talked about this annotation in

the initial article of the series,

but as a quick reminder:

it tells Graal to apply the loop unrolling

optimization when JIT-compiling this method.

That’s safe, because every function call Node will always have the same number of children representing the function’s arguments –

for example, for an expression like Math.pow(x, y),

it will always be 2, and that number can’t ever change,

regardless of what are the exact values of x and y.

FunctionDispatchNode

So finally, we get to the function dispatch Node.

What specializations do we want to write for function calls?

We could simply invoke the call() method on the CallTarget

in the FunctionObject we get after evaluating the target expression,

but that wouldn’t be optimal from a performance perspective.

Instead, we want to use one of two important classes from Truffle to make the call:

either DirectCallNode, or IndirectCallNode.

It’s important that all function calls in a Truffle interpreter go through one of these two intermediaries,

as they are recognized by Graal,

and optimized in a special way.

As their names suggest,

which one to use depends on how stable the target of a given function call expression is.

Most of the time, the targets in function call expressions are pretty static,

and they will always evaluate to the same function;

this is the case for code like f(x, y);,

where f is a global constant.

In those cases, we can use DirectCallNode.

However, it’s also possible that the target expression is more dynamic.

For example, let’s take the same f(x, y); code as above,

but now imagine f is not a global variable,

but instead an argument of a function.

In that case, any function can be passed as the f argument at runtime,

and so we need to use the IndirectCallNode.

(I understand we could probably get away with only the first case for EasyScript at this moment in the article series, as we don’t support any functions that take other functions as arguments; but I want to implement the entirety of the function call semantics in this part anyway, as that will save us from coming back to this topic later in the series)

Finally, there is also the possibility that we get called with something that’s not a function at all;

for example, imagine if our code passes undefined as the f argument from above.

In that case, we need to fail with an exception.

So, our FunctionDispatchNode looks as follows:

import com.oracle.truffle.api.dsl.Cached;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.dsl.Fallback;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.dsl.Specialization;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.nodes.DirectCallNode;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.nodes.IndirectCallNode;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.nodes.Node;

public abstract class FunctionDispatchNode extends Node {

public abstract Object executeDispatch(Object function, Object[] arguments);

@Specialization(guards = "function.callTarget == directCallNode.getCallTarget()", limit = "2")

protected static Object dispatchDirectly(

FunctionObject function, Object[] arguments,

@Cached("create(function.callTarget)") DirectCallNode directCallNode) {

return directCallNode.call(arguments);

}

@Specialization(replaces = "dispatchDirectly")

protected static Object dispatchIndirectly(

FunctionObject function, Object[] arguments,

@Cached IndirectCallNode indirectCallNode) {

return indirectCallNode.call(function.callTarget, arguments);

}

@Fallback

protected static Object targetIsNotAFunction(

Object nonFunction, Object[] arguments) {

throw new EasyScriptException("'" + nonFunction + "' is not a function");

}

}

There are a few interesting things about this class.

The first one is that it’s not part of our expression Node hierarchy –

it doesn’t extend EasyScriptExprNode.

There are two reason for that.

One, there’s no sensible way to specialize on the return type of a function call –

the only reasonable thing you can do is call the function,

and then check what type it returns,

but our expression Nodes will do that anyway,

so adding additional execute*() methods here would add no value.

And two, because it doesn’t extend EasyScriptExprNode,

it can define its own execute*() method.

You probably noticed that its signature is different from other execute*()

methods we’ve seen so far:

it skips the VirtualFrame argument,

and instead declares it takes two values as arguments:

the called function, and the arguments it was called with.

We make the execute*() methods take arguments directly,

as this Node has no children,

and thus the Truffle DSL wouldn’t know where to get the arguments to call our @Specialization methods otherwise.

Speaking of the Truffle DSL,

this class uses a few more its features we haven’t seen before besides the non-standard execute*() method.

Let’s start with the @Cached annotation.

It allows saving a given value when a specialization is first instantiated.

To specify what value should be cached,

you use a string-based DSL in the value attribute of the annotation that’s basically a simplified subset of Java.

In our case, in the dispatchDirectly() specialization,

we instantiate a new DirectNode by calling its create() static factory method,

and passing it the callTarget field of the FunctionObject that’s being invoked.

Interestingly, the @Cached annotation has a default for the value attribute,

and it’s calling the static factory create() method of the type of the parameter it annotates –

we use it in the second specialization, dispatchIndirectly(),

to create an instance of IndirectCallNode.

The next new Truffle DSL feature in FunctionDispatchNode is the guards attribute of @Specialization.

It allows adding extra assertions to the code that verifies at runtime that the given specialization is safe to apply.

Up to this point, the only conditions we placed on specializations were that its sub-expressions had to evaluate to a specific type;

for example, both of them had to be ints, or both of them had to be doubles.

But the Truffle DSL allows adding more complex conditions before a given specialization is considered safe by using the guards attribute.

It uses the same string-based, Java-subset DSL that @Cached uses,

but here the expression needs to evaluate to true in order for the specialization to be applied.

In our case, in dispatchDirectly(),

we make sure the function being invoked did not change from the last call,

by comparing its callTarget with the CallTarget in the DirectCallNode we cached.

If they are different, that means the target of the function call has changed,

and we need to activate a new specialization

(which might be a second instance of the dispatchDirectly() method,

or one of the other two methods in FunctionDispatchNode).

And the final new Truffle DSL feature in FunctionDispatchNode is the limit attribute.

It allows you to specify that,

after a certain amount of instantiations,

we should stop trying to activate specializations represented by this method.

For our dispatchDirectly() method,

we make it "2", meaning we will consider a call site direct if it has at most two different CallTargets.

Once we see a third target,

we no longer create new DirectCallNodes,

and instead switch to the dispatchIndirectly() specialization.

Note that simply exceeding the limit does not automatically remove the specializations that were previously activated,

but since we annotated dispatchIndirectly() with @Specialization(replaces = "dispatchDirectly"),

this will be what happens in our case,

which is the behavior we want.

The limit attribute uses the same string-based, Java-subset DSL that @Cached and guards do,

instead of a simple int,

which means the limit can be calculated dynamically at runtime,

it doesn’t have to be a static value

(although, of course, it can be, like in our case).

Note that the default value for that attribute in Truffle is "3".

You might have also noticed that the @Specialization methods are static!

This is allowed by the Truffle DSL,

as specialization methods usually only use their arguments,

and no other state from the Node

(although there are exceptions,

like the GlobalVarAssignmentExprNode from the

previous article

that needs access to the variable name stored in a given Node).

Since specialization methods are typically very short,

they are usually inlined anyway during partial evaluation,

so there shouldn’t really be any performance advantage in making them static.

It’s more of a convention used in Truffle for Nodes that have no children,

like our FunctionDispatchNode.

Invoked Nodes

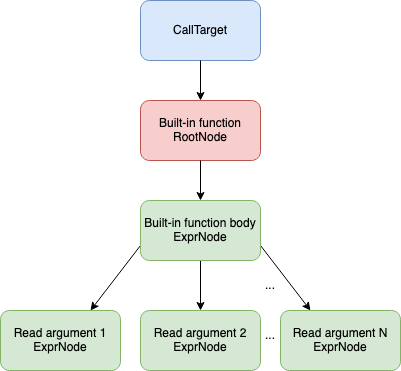

So, that’s how the Nodes for invoking functions work. Let’s now explore how does the opposite side, the Nodes being invoked, look like.

From part 1,

we know that a CallTarget contains a RootNode,

which in turn contains the actual Node or Nodes representing our code.

In the case of built-in functions,

we only need a single Node instance to represent any function,

because we’ll be writing the implementation of that function ourselves in Java.

This single function implementation Node will have children,

used for retrieving the values of the arguments the function was called with.

It will have a number of children equal to the number of arguments it takes.

This diagram shows the above Node hierarchy visually:

FunctionRootNode

The function RootNode is extremely simple –

it just wraps an EasyScriptExprNode representing the body of our function:

import com.oracle.truffle.api.frame.VirtualFrame;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.nodes.RootNode;

public final class FunctionRootNode extends RootNode {

@SuppressWarnings("FieldMayBeFinal")

@Child

private EasyScriptExprNode functionBodyExpr;

public FunctionRootNode(EasyScriptTruffleLanguage truffleLanguage,

EasyScriptExprNode functionBodyExpr) {

super(truffleLanguage);

this.functionBodyExpr = functionBodyExpr;

}

@Override

public Object execute(VirtualFrame frame) {

return this.functionBodyExpr.executeGeneric(frame);

}

}

ReadFunctionArgExprNode

The expression Node for reading the values of the arguments the function has been called with is also simple.

It’s very significant though,

as this is the first Node in the series that actually uses the VirtualFrame argument to its execute*() methods!

The arguments the function was called with will be inserted into the arguments array of the VirtualFrame that the CallTarget creates when its call() method is invoked.

So, we have to read the function’s argument from there:

import com.oracle.truffle.api.frame.VirtualFrame;

public final class ReadFunctionArgExprNode extends EasyScriptExprNode {

private final int index;

public ReadFunctionArgExprNode(int index) {

this.index = index;

}

@Override

public Object executeGeneric(VirtualFrame frame) {

Object[] arguments = frame.getArguments();

return this.index < arguments.length ? arguments[this.index] : Undefined.INSTANCE;

}

}

The interesting part in this Node is correctly implementing JavaScript call semantics.

In JavaScript, unlike in most languages, you can call a function with arbitrary many arguments,

regardless of how many arguments it actually declares.

If the call has more arguments than the function declares,

any extra arguments are simply discarded;

if the call has fewer arguments than the function declares,

all arguments that were not provided are initialized with undefined.

This is what we implement in ReadFunctionArgExprNode –

if the frame doesn’t contain an argument for the index our Node represents

(which means the calling expression didn’t contain that many arguments),

we return Undefined.INSTANCE.

The Math.abs function

Finally, we can write the Node that represents our abs() function.

Of course, we want to use specializations to define it more efficiently in case the argument is an int:

import com.oracle.truffle.api.dsl.Fallback;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.dsl.NodeChild;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.dsl.Specialization;

@NodeChild(value = "argument", type = ReadFunctionArgExprNode.class)

public abstract class AbsFunctionBodyExprNode extends EasyScriptExprNode {

@Specialization(rewriteOn = ArithmeticException.class)

protected int intAbs(int argument) {

return argument < 0 ? Math.negateExact(argument) : argument;

}

@Specialization(replaces = "intAbs")

protected double doubleAbs(double argument) {

return Math.abs(argument);

}

@Fallback

protected double nonNumberAbs(Object argument) {

return Double.NaN;

}

}

You might be surprised by how the code handles abs for ints –

can’t we just return -argument if it’s negative,

what’s the deal with Math.negateExact()?

The reason for the code looking like it does is the edge case with Integer.MIN_VALUE.

You see, the absolute value of Integer.MIN_VALUE actually doesn’t fit in an int

(because of the

two’s complement

way of representing integers).

For that reason, we have to switch to double if abs() is called with Integer.MIN_VALUE,

and using negateExact() allows us to easily do that,

as it will throw ArithmeticException when negating Integer.MIN_VALUE.

TruffleLanguage

And finally, in order for our variable resolution to find the Math.abs function from above,

we need to add a variable with the name "Math.abs" to our global scope that we created in the

previous article,

and point it to the correct FunctionObject.

We do that in the createContext() method of our TruffleLanguage implementation:

import com.oracle.truffle.api.CallTarget;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.TruffleLanguage;

@TruffleLanguage.Registration(id = "ezs", name = "EasyScript")

public final class EasyScriptTruffleLanguage extends

TruffleLanguage<EasyScriptLanguageContext> {

@Override

protected CallTarget parse(ParsingRequest request) throws Exception {

List<EasyScriptStmtNode> stmts = EasyScriptTruffleParser.parse(request.getSource().getReader());

var programRootNode = new ProgramRootNode(this, stmts);

return programRootNode.getCallTarget();

}

@Override

protected EasyScriptLanguageContext createContext(Env env) {

var context = new EasyScriptLanguageContext();

// add the built-in functions to the global scope

var absFuncRootNode = new FunctionRootNode(this,

AbsFunctionBodyExprNodeGen.create(new ReadFunctionArgExprNode(0)));

context.globalScopeObject.newConstant("Math.abs",

new FunctionObject(absFuncRootNode.getCallTarget()));

return context;

}

@Override

protected Object getScope(EasyScriptLanguageContext context) {

return context.globalScopeObject;

}

}

With this in place, we can now write a unit test calling our abs() function!

import org.graalvm.polyglot.Value;

import org.junit.jupiter.api.Test;

import static org.junit.jupiter.api.Assertions.assertEquals;

class FunctionsTest {

@Test

void calling_Math_abs_works() {

Value result = this.context.eval("ezs", "Math.abs(-2)");

assertEquals(2, result.asInt());

}

// ...

}

NodeFactory

While we made function calls work,

there’s one small wrinkle.

Let’s look at the code that defines the Math.abs function in our TruffleLanguage again:

context.globalScopeObject.newConstant(

"Math.abs",

new FunctionObject(new FunctionRootNode(this,

AbsFunctionBodyExprNodeGen.create(new ReadFunctionArgExprNode(0))).getCallTarget()));

That is quite a big expression! Imagine we wanted to support not 2, but 20, or 200, built-in functions in our language. The amount of code needed to add all of those functions to the global scope would be huge!

Now, looking at the code above, it’s clear that the only abs()-specific parts are "Math.abs" and AbsFunctionBodyExprNodeGen.create() –

the remainder of the expression parts will always be the same for each function

(with the slight detail of possibly needing a different number of ReadFunctionArgExprNodes,

depending on how many arguments a given function takes).

So, we would like to create a utility method for adding these functions to the global scope,

which would save a lot of code.

But if you try to write that utility method,

you quickly realize there’s a problem:

there’s no concept of a “factory” of function body Nodes.

You only have the create() methods for the function Nodes,

and those create() methods take different number of arguments,

depending on how many arguments a given function takes.

So, there’s no common type shared among all function Node classes that you can use in the signature of your utility method.

Fortunately, the authors of the Truffle DSL realized this is a problem,

and they came up with a solution.

You can annotate your Node class with the @GenerateNodeFactory annotation,

and the Truffle DSL will generate a class,

called <YourNodeClass>Factory,

that implements the interface NodeFactory<YourNodeClass>.

That interface contains a create() method that can be used to instantiate your Node.

This is the missing type that you can use in the declaration of your helper method.

Since annotations are inherited in Truffle,

it’s good practice to create a common superclass of all the built-in function body Nodes,

and annotate that with @GenerateNodeFactory,

to reduce duplication:

import com.oracle.truffle.api.dsl.GenerateNodeFactory;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.dsl.NodeChild;

@NodeChild(value = "arguments", type = ReadFunctionArgExprNode[].class)

@GenerateNodeFactory

public abstract class BuiltInFunctionBodyExprNode extends EasyScriptExprNode {

}

We define that the Node has a variable amount of children with @NodeChild,

because each function takes a different amount of arguments.

We can make our pow() function body Node inherit from this class:

import com.oracle.truffle.api.dsl.Fallback;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.dsl.Specialization;

public abstract class PowFunctionBodyExprNode extends BuiltInFunctionBodyExprNode {

@Specialization(guards = "exponent >= 0", rewriteOn = ArithmeticException.class)

protected int intPow(int base, int exponent) {

int ret = 1;

for (int i = 0; i < exponent; i++) {

ret = Math.multiplyExact(ret, base);

}

return ret;

}

@Specialization(replaces = "intPow")

protected double doublePow(double base, double exponent) {

return Math.pow(base, exponent);

}

@Fallback

protected double nonNumberPow(Object base, Object exponent) {

return Double.NaN;

}

}

Note that we use the guards attribute of @Specialization again,

because we know only non-negative exponents can return an int result for pow().

And with this, we can now write our helper method inside EasyScriptTruffleLanguage:

import com.oracle.truffle.api.CallTarget;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.TruffleLanguage;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.dsl.NodeFactory;

@TruffleLanguage.Registration(id = "ezs", name = "EasyScript")

public final class EasyScriptTruffleLanguage extends

TruffleLanguage<EasyScriptLanguageContext> {

// ...

@Override

protected EasyScriptLanguageContext createContext(Env env) {

var context = new EasyScriptLanguageContext();

this.defineBuiltInFunction(context, "Math.abs",

AbsFunctionBodyExprNodeFactory.getInstance());

this.defineBuiltInFunction(context, "Math.pow",

PowFunctionBodyExprNodeFactory.getInstance());

return context;

}

private void defineBuiltInFunction(EasyScriptLanguageContext context, String name,

NodeFactory<? extends BuiltInFunctionBodyExprNode> nodeFactory) {

ReadFunctionArgExprNode[] functionArguments = IntStream.range(0, nodeFactory.getExecutionSignature().size())

.mapToObj(i -> new ReadFunctionArgExprNode(i))

.toArray(ReadFunctionArgExprNode[]::new);

var builtInFuncRootNode = new FunctionRootNode(this,

nodeFactory.createNode((Object) functionArguments));

context.globalScopeObject.newConstant(name,

new FunctionObject(builtInFuncRootNode.getCallTarget()));

}

}

We use the getExecutionSignature() method of NodeFactory to find out how many arguments does the function take

(the Truffle DSL will infer that from the number of arguments the @Specialization methods take in a given function body Node class),

and create that many ReadFunctionArgExprNodes for the children of a given function Node.

And now, we can unit test the pow() function:

import org.graalvm.polyglot.Value;

import org.junit.jupiter.api.Test;

import static org.junit.jupiter.api.Assertions.assertEquals;

class FunctionsTest {

@Test

void calling_Math_pow_works() {

Value result = this.context.eval("ezs", "Math.pow(2, 3)");

assertEquals(8, result.asInt());

}

// ...

}

FunctionObject as a polyglot value

At this point, the only thing remaining is making our FunctionObject a good citizen of the GraalVM polyglot ecosystem.

Since we can now return functions from EasyScript

(in code like var a = Math.abs; a),

we should make sure we make them polyglot values.

Like we did in the

previous part for Undefined,

this means implementing the TruffleObject marker interface,

and overriding message from the

interop library.

In particular, in this case, we’re interested in the

isExecutable()

and execute() messages,

so that our functions can be called from other languages.

Here, the FunctionDispatchNode will be very helpful –

since it contains all of the logic of specializing on function calls,

we can just re-use it here for polyglot calls too.

There’s one important thing we need to handle in FunctionObject though.

Right now, our EasyScript language only supports values of type int, double, Undefined and FunctionObject.

However, since we’re exposing an execute() message to other languages,

this means the other languages can pass any values to our functions,

like strings, or objects of an arbitrary class.

Our FunctionObject should take that into account before calling our function body:

import com.oracle.truffle.api.CallTarget;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.interop.InteropLibrary;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.interop.TruffleObject;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.library.ExportLibrary;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.library.ExportMessage;

@ExportLibrary(InteropLibrary.class)

public final class FunctionObject implements TruffleObject {

public final CallTarget callTarget;

private final FunctionDispatchNode functionDispatchNode;

public FunctionObject(CallTarget callTarget) {

this.callTarget = callTarget;

this.functionDispatchNode = FunctionDispatchNodeGen.create();

}

@ExportMessage

boolean isExecutable() {

return true;

}

@ExportMessage

Object execute(Object[] arguments) {

for (Object argument : arguments) {

if (!this.isEasyScriptValue(argument)) {

throw new EasyScriptException("'" + argument + "' is not an EasyScript value");

}

}

return this.functionDispatchNode.executeDispatch(this, arguments);

}

private boolean isEasyScriptValue(Object argument) {

return EasyScriptTypeSystemGen.isImplicitDouble(argument) ||

argument == Undefined.INSTANCE ||

argument instanceof FunctionObject;

}

}

As you can see, in EasyScript, I’ve decided to just error out for any values not supported by the language.

This is probably a little too harsh,

and, when implementing your own language,

you might consider relaxing that requirement,

and doing some conversions

(for example, it would probably make sense to convert values of types byte and short to ints,

float values to double, etc.).

However, since EasyScript is just an example language,

I’ve decided to go with the simplest solution possible.

And with this, we can actually call EasyScript functions straight from Java!

import org.graalvm.polyglot.Value;

import org.junit.jupiter.api.Test;

import static org.junit.jupiter.api.Assertions.assertEquals;

import static org.junit.jupiter.api.Assertions.assertTrue;

class FunctionsTest {

@Test

void an_EasyScript_function_can_be_called_from_Java() {

Value mathAbs = this.context.eval("ezs", "Math.abs");

assertTrue(mathAbs.canExecute());

Value result = mathAbs.execute(-3);

assertEquals(3, result.asInt());

}

// ...

}

Summary

I hope you can see now why I’ve waited to tackle function calls until part 6 of the series – they are one of the more complex areas of Truffle, mainly because optimizing function calls is such a critical part of writing a high-performance language implementation.

As usual, all code from the article is available on GitHub.

In the next part of the series, we continue with the topic of functions – we will learn how to implement function definitions.

This article is part of a tutorial on GraalVM's Truffle language implementation framework.

- Part 0 – what is Truffle

- Part 1 – setup, Nodes, CallTarget

- Part 2 – introduction to specializations

- Part 3 – specializations with Truffle DSL, TypeSystem

- Part 4 – parsing, and the TruffleLanguage class

- Part 5 – global variables

- Part 6 – static function calls

- Part 7 – function definitions

- Part 8 – conditionals, loops, control flow

- Part 9 – performance benchmarking

- Part 10 – arrays, read-only properties

- Part 11 – strings, static method calls

- Part 12 – classes 1: methods, new

- Part 13 – classes 2: fields, this, constructors

- Part 14 – classes 3: inheritance, super

- Part 15 – exceptions

- Part 16 – debuggers