Graal Truffle tutorial part 12 – classes 1: methods, new

This article is part of a tutorial on GraalVM's Truffle language implementation framework.

- Part 0 – what is Truffle

- Part 1 – setup, Nodes, CallTarget

- Part 2 – introduction to specializations

- Part 3 – specializations with Truffle DSL, TypeSystem

- Part 4 – parsing, and the TruffleLanguage class

- Part 5 – global variables

- Part 6 – static function calls

- Part 7 – function definitions

- Part 8 – conditionals, loops, control flow

- Part 9 – performance benchmarking

- Part 10 – arrays, read-only properties

- Part 11 – strings, static method calls

- Part 12 – classes 1: methods, new

- Part 13 – classes 2: fields, this, constructors

- Part 14 – classes 3: inheritance, super

- Part 15 – exceptions

- Part 16 – debuggers

In this part of the Truffle tutorial,

we finally start adding support for defining classes to EasyScript,

our simplified JavaScript implementation.

Since classes are one of the most complex features of any programming language,

we will cover their implementation over multiple articles.

In this first part, we will handle class declarations containing (instance) methods,

and instantiating objects of these classes with the new operator.

Class declarations

Grammar

In order to support class declarations, we add a new kind of statement to our language’s ANTLR grammar (in JavaScript, classes can also be defined inside an expression, but we won’t bother supporting that feature, as it’s purely a parsing matter).

In the class declaration itself,

we will only support (public) instance methods

in this part of the series.

These look very similar to function definitions that we support since

part 7,

just without the function keyword:

an identifier that represents the method’s name, then a list of method arguments in parentheses,

and finally the method body between a pair of braces.

To reduce duplication, we’ll extract a new non-terminal from the function production,

and use it in both places:

stmt : 'function' subroutine_decl ';'? #FuncDeclStmt

| 'class' ID '{' class_member* '}' ';'? #ClassDeclStmt

// ...

;

class_member : subroutine_decl ;

subroutine_decl : name=ID '(' args=func_args ')' '{' stmt* '}' ;

func_args : (ID (',' ID)* )? ;

Parsing a class declaration means handling each method declaration.

Fortunately, here too we can re-use the Node for function declarations.

Currently, it saves the functions as properties of the global scope DynamicObject;

in the case of classes, almost everything stays the same,

but we now need to save the functions as properties of a different DynamicObject,

the one that represents the class itself.

We will call that object the class prototype

(for reasons we’ll get to below):

public final class EasyScriptTruffleParser {

// ...

private EasyScriptStmtNode parseClassDeclStmt(EasyScriptParser.ClassDeclStmtContext classDeclStmt) {

if (this.state == ParserState.FUNC_DEF) {

// we do not allow nesting classes inside functions at the moment

// (in theory, we could handle it by assigning the class object to a local variable,

// but the additional complexity doesn't seem worth it)

throw new EasyScriptException("classes nested in functions are not supported in EasyScript");

}

String className = classDeclStmt.ID().getText();

var classPrototype = new ClassPrototypeObject(this.objectShape, className);

List<FuncDeclStmtNode> classMethods = new ArrayList<>();

for (var classMember : classDeclStmt.class_member()) {

classMethods.add(this.parseSubroutineDecl(classMember.subroutine_decl(),

new DynamicObjectReferenceExprNode(classPrototype)));

}

return GlobalVarDeclStmtNodeGen.create(

GlobalScopeObjectExprNodeGen.create(),

new ClassDeclExprNode(classMethods, classPrototype),

className, DeclarationKind.LET);

}

private FuncDeclStmtNode parseFuncDeclStmt(EasyScriptParser.FuncDeclStmtContext funcDeclStmt) {

return this.parseSubroutineDecl(funcDeclStmt.subroutine_decl(),

GlobalScopeObjectExprNodeGen.create());

}

private FuncDeclStmtNode parseSubroutineDecl(EasyScriptParser.Subroutine_declContext subroutineDecl,

EasyScriptExprNode containerObjectExpr) {

// virtually unchanged from the last part of the series...

In order to give FuncDeclStmtNode access to that class prototype object,

we create a new expression Node that simply returns a reference to the object it was given:

import com.oracle.truffle.api.frame.VirtualFrame;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.object.DynamicObject;

public final class DynamicObjectReferenceExprNode extends EasyScriptExprNode {

private final DynamicObject dynamicObject;

public DynamicObjectReferenceExprNode(DynamicObject dynamicObject) {

this.dynamicObject = dynamicObject;

}

@Override

public DynamicObject executeGeneric(VirtualFrame frame) {

return this.dynamicObject;

}

}

And then we pass the FuncDeclStmtNode responsible for methods an instance of DynamicObjectReferenceExprNode,

as opposed to an instance of GlobalScopeObjectExprNode that is passed to FuncDeclStmtNodes

that are used for (global) functions.

FuncDeclStmtNode itself is identical to how it looked since

part 10 of the series,

just with the names slightly changed to reflect it’s now more generic than just handling global functions:

import com.oracle.truffle.api.CompilerDirectives;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.CompilerDirectives.CompilationFinal;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.dsl.NodeChild;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.dsl.NodeField;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.dsl.Specialization;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.frame.FrameDescriptor;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.library.CachedLibrary;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.object.DynamicObject;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.object.DynamicObjectLibrary;

@NodeChild(value = "containerObjectExpr", type = EasyScriptExprNode.class)

@NodeField(name = "funcName", type = String.class)

@NodeField(name = "frameDescriptor", type = FrameDescriptor.class)

@NodeField(name = "funcBody", type = UserFuncBodyStmtNode.class)

@NodeField(name = "argumentCount", type = int.class)

public abstract class FuncDeclStmtNode extends EasyScriptStmtNode {

protected abstract String getFuncName();

protected abstract FrameDescriptor getFrameDescriptor();

protected abstract UserFuncBodyStmtNode getFuncBody();

protected abstract int getArgumentCount();

@CompilationFinal

private FunctionObject cachedFunction;

@Specialization(limit = "2")

protected Object declareFunction(

DynamicObject containerObject,

@CachedLibrary("containerObject") DynamicObjectLibrary objectLibrary) {

if (this.cachedFunction == null) {

CompilerDirectives.transferToInterpreterAndInvalidate();

var truffleLanguage = this.currentTruffleLanguage();

var funcRootNode = new StmtBlockRootNode(truffleLanguage, this.getFrameDescriptor(), this.getFuncBody());

var callTarget = funcRootNode.getCallTarget();

this.cachedFunction = new FunctionObject(callTarget, this.getArgumentCount());

}

objectLibrary.putConstant(containerObject, this.getFuncName(), this.cachedFunction, 0);

return Undefined.INSTANCE;

}

}

Nodes

The expression Node that implements the class declaration itself is very simple.

It just executes all of the FuncDeclStmtNodes that correspond to the methods of the class,

and returns the class prototype object,

which is saved as a global variable with a name equal to the class name by GlobalVarDeclStmtNode:

import com.oracle.truffle.api.frame.VirtualFrame;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.nodes.ExplodeLoop;

public final class ClassDeclExprNode extends EasyScriptExprNode {

@Children

private final FuncDeclStmtNode[] classMethodDecls;

private final ClassPrototypeObject classPrototypeObject;

public ClassDeclExprNode(List<FuncDeclStmtNode> classMethodDecls,

ClassPrototypeObject classPrototypeObject) {

this.classMethodDecls = classMethodDecls.toArray(FuncDeclStmtNode[]::new);

this.classPrototypeObject = classPrototypeObject;

}

@Override

@ExplodeLoop

public ClassPrototypeObject executeGeneric(VirtualFrame frame) {

for (FuncDeclStmtNode classMethodDecl : this.classMethodDecls) {

classMethodDecl.executeStatement(frame);

}

return this.classPrototypeObject;

}

}

ClassPrototypeObject is an extremely simple Truffle DynamicObject,

that only saves the class name it corresponds to:

import com.oracle.truffle.api.interop.InteropLibrary;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.library.ExportLibrary;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.library.ExportMessage;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.object.DynamicObject;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.object.Shape;

@ExportLibrary(InteropLibrary.class)

public final class ClassPrototypeObject extends DynamicObject {

private final String className;

public ClassPrototypeObject(Shape shape, String className) {

super(shape);

this.className = className;

}

@Override

public String toString() {

return "[class " + this.className + "]";

}

@ExportMessage

Object toDisplayString(@SuppressWarnings("unused") boolean allowSideEffects) {

return this.toString();

}

}

new expressions

Of course, class declarations are just half the story –

the other half is actually creating instances of those classes.

For that purpose, many object-oriented languages, and that includes JavaScript,

use the new expression.

Parsing

A new expression consists of the new keyword,

a sub-expression that has to evaluate to the class prototype object

that we saved as a global variable in the class declaration statement above,

and then arguments for the constructor of the class,

in parentheses – similarly to a function call

(while we won’t yet support constructors in this part of the series,

we still want to allow passing arguments to new,

so that we don’t have to change its grammar in later parts of the series).

The tricky part about parsing new is making sure it binds stronger than the call expression,

so that new A().m() is parsed as (new A()).m(), instead of new (A().m)().

In order to achieve that, we split the existing fifth level of expression precedence into two,

and put new on the last, sixth, level:

expr5 : expr5 '.' ID #PropertyReadExpr5

| arr=expr5 '[' index=expr1 ']' #ArrayIndexReadExpr5

| expr5 '(' (expr1 (',' expr1)*)? ')' #CallExpr5

| expr6 #PrecedenceSixExpr5

;

expr6 : literal #LiteralExpr6

| ID #ReferenceExpr6

| '[' (expr1 (',' expr1)*)? ']' #ArrayLiteralExpr6

| 'new' constr=expr6 ('(' (expr1 (',' expr1)*)? ')')? #NewExpr6

| '(' expr1 ')' #PrecedenceOneExpr6

;

...

The last interesting part about parsing new

is that in JavaScript, unlike in virtually all other languages with this operator,

the parentheses for the arguments are optional if there are no arguments passed to the class’ constructor –

so, new A is the same as new A().

Node

The implementation of the new Node is a little tricky.

The new Node needs a variable amount of children

(the arguments passed to the class’ constructor),

but at the same time, we want to use specializations in it,

in order to make sure the constructor expression resolves to an instance of ClassPrototypeObject.

However, as we already covered in part 6

when discussing function call expressions,

you can’t use the Truffle DSL to write specializations that take a collection of values as an argument

that are the result of evaluating a variable amount of child Nodes,

like the new Node has.

Fortunately, there’s also a different way to use the Truffle DSL that is helpful in these situations.

First of all, you can define a constructor in your abstract Node class.

The DSL will call that constructor in the generated subclass Node,

and will add the constructor arguments to the create()

static factory method it generates on the subclass.

And secondly, you can use the @Executed annotation

to designate that a given child Node should be executed before the parent Node,

and the result of executing it should be passed to the specialization methods.

That’s very similar to using the @NodeChild annotation,

but the difference is that with @Executed,

the arguments to create() and the Node’s fields can be different,

because you can translate between the two in the constructor.

And this is exactly what we need here –

we want to receive a List of expression Nodes in the constructor

(from the parser),

but save them as an array in the field

(as the @Children annotation requires that).

Putting it all together, the implementation of the new Node looks as follows:

import com.oracle.truffle.api.dsl.Executed;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.dsl.Fallback;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.dsl.Specialization;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.frame.VirtualFrame;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.nodes.ExplodeLoop;

public abstract class NewExprNode extends EasyScriptExprNode {

@Child

@Executed

protected EasyScriptExprNode constructorExpr;

@Children

private final EasyScriptExprNode[] args;

protected NewExprNode(EasyScriptExprNode constructorExpr, List<EasyScriptExprNode> args) {

this.constructorExpr = constructorExpr;

this.args = args.toArray(EasyScriptExprNode[]::new);

}

@Specialization

protected Object instantiateObject(VirtualFrame frame, ClassPrototypeObject classPrototypeObject) {

this.consumeArguments(frame);

return new ClassInstanceObject(classPrototypeObject);

}

@Fallback

protected Object instantiateNonConstructor(VirtualFrame frame, Object object) {

this.consumeArguments(frame);

throw new EasyScriptException("'" + object + "' is not a constructor");

}

@ExplodeLoop

private void consumeArguments(VirtualFrame frame) {

for (int i = 0; i < this.args.length; i++) {

this.args[i].executeGeneric(frame);

}

}

}

Since we don’t support constructors yet in this part of the series, we don’t need the values of the arguments for anything. However, since expressions can contain side effects (like assignment), we evaluate them, and just discard the values they produce.

Class instances

So, the last thing remaining is the implementation of ClassInstanceObject.

A naive approach might be to store all methods as DynamicObject

properties of the instance object itself.

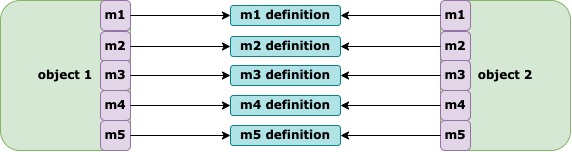

For example, let’s imagine we have a class that defines 5 methods,

called m1 through m5.

If we stored the methods on the object directly,

it would look something like this:

And while that would work, there is a pretty obvious problem with this solution: each object contains 5 references inside of it, even though all of those references point at the same method implementations. That makes each instance of the class take a lot of memory – and there can be potentially thousands or even millions of these instances created during the lifetime of the program.

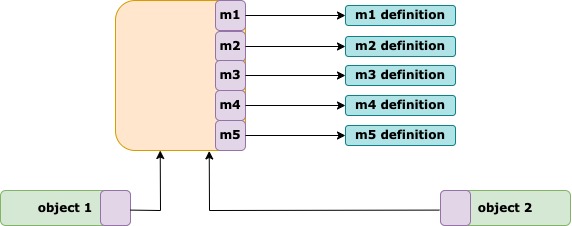

So, to solve this issue, it’s typical in implementations of object-oriented languages to store class methods in a single separate object, and each instance points to that single object:

This reduces the memory footprint of each object instance, at the cost of an additional lookup when searching for a particular method – however, most modern runtimes of object-oriented languages are really good at eliminating this overhead, and we’ll see some techniques to do that in Truffle in later parts of the series.

Interestingly, that orange box in the diagram above that contains the instance methods is present in virtually every object-oriented programming language, but it has many different names. C++ calls it a vtable (short for “virtual method table”, as instance methods are called “virtual functions” in that language). In Java and Python, this is referred to as the class object. In Ruby, it’s called the metaclass.

In JavaScript, we call it a prototype,

and that’s the reason we named ClassPrototypeObject what we did.

The name comes from the particular way inheritance works in JavaScript

(called, no surprise, prototypical inheritance),

which we will cover in more detail in later parts of the series.

So, our ClassInstanceObject has to implement the methods from the InteropLibrary

by delegating all property reads to the underlying ClassPrototypeObject:

import com.oracle.truffle.api.interop.InteropLibrary;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.interop.TruffleObject;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.interop.UnknownIdentifierException;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.library.CachedLibrary;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.library.ExportLibrary;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.library.ExportMessage;

import com.oracle.truffle.api.object.DynamicObjectLibrary;

@ExportLibrary(InteropLibrary.class)

public final class ClassInstanceObject implements TruffleObject {

// this can't be private, because it's used in specialization guard expressions

final ClassPrototypeObject classPrototypeObject;

public ClassInstanceObject(ClassPrototypeObject classPrototypeObject) {

this.classPrototypeObject = classPrototypeObject;

}

@Override

public String toString() {

return "[object Object]";

}

@ExportMessage

Object toDisplayString(@SuppressWarnings("unused") boolean allowSideEffects) {

return this.toString();

}

@ExportMessage

boolean hasMembers() {

return true;

}

@ExportMessage

boolean isMemberReadable(String member,

@CachedLibrary("this.classPrototypeObject") DynamicObjectLibrary dynamicObjectLibrary) {

return dynamicObjectLibrary.containsKey(this.classPrototypeObject, member);

}

@ExportMessage

Object readMember(String member,

@CachedLibrary("this.classPrototypeObject") DynamicObjectLibrary dynamicObjectLibrary)

throws UnknownIdentifierException {

Object value = dynamicObjectLibrary.getOrDefault(this.classPrototypeObject, member, null);

if (value == null) {

throw UnknownIdentifierException.create(member);

}

return value;

}

@ExportMessage

Object getMembers(@SuppressWarnings("unused") boolean includeInternal,

@CachedLibrary("this.classPrototypeObject") DynamicObjectLibrary dynamicObjectLibrary) {

return new MemberNamesObject(dynamicObjectLibrary.getKeyArray(this.classPrototypeObject));

}

}

This is also why, in many languages, it’s legal to have a field and a method with the same name – it’s because methods are kept in the class object, while fields are saved in the object directly. Of course, in JavaScript, that’s not allowed, because it’s a dynamically-typed language with first-class functions, and so there’s no distinction between fields and methods – a method is simply a field with a function as the value. It’s just that fields assigned directly on the object override the fields from the prototype. We will handle this in EasyScript when we handle prototypical inheritance later in the series.

Benchmark

Now with all the pieces in place,

we can write a benchmark that calls a simple add()

method of a class we define:

public class InstanceMethodBenchmark extends TruffleBenchmark {

private static final String ADDER_CLASS = "" +

"class Adder { " +

" add(a, b) { " +

" return a + b; " +

" } " +

"}";

@Override

public void setup() {

super.setup();

this.truffleContext.eval("ezs", ADDER_CLASS);

this.truffleContext.eval("js", ADDER_CLASS);

// ...

}

// ...

}

We’ll have two variants of the benchmark.

In the first one, we will create the instance of the Adder

class inside the main loop:

import org.openjdk.jmh.annotations.Benchmark;

public class InstanceMethodBenchmark extends TruffleBenchmark {

private static final int INPUT = 1_000_000;

private static final String COUNT_METHOD_PROP_ALLOC_INSIDE_FOR = "" +

"function countMethodPropAllocInsideFor(n) { " +

" var ret = 0; " +

" for (let i = 0; i < n; i = i + 1) { " +

" ret = new Adder().add(ret, 1); " +

" } " +

" return ret; " +

"}";

@Override

public void setup() {

// ...

this.truffleContext.eval("ezs", COUNT_METHOD_PROP_ALLOC_INSIDE_FOR);

this.truffleContext.eval("js", COUNT_METHOD_PROP_ALLOC_INSIDE_FOR);

}

@Benchmark

public int count_method_prop_alloc_inside_for_ezs() {

return this.truffleContext.eval("ezs", "countMethodPropAllocInsideFor(" + INPUT + ");").asInt();

}

@Benchmark

public int count_method_prop_alloc_inside_for_js() {

return this.truffleContext.eval("js", "countMethodPropAllocInsideFor(" + INPUT + ");").asInt();

}

// ...

}

And in the second variant,

we create the instance of the Adder class outside the loop:

import org.openjdk.jmh.annotations.Benchmark;

public class InstanceMethodBenchmark extends TruffleBenchmark {

private static final String COUNT_METHOD_PROP_ALLOC_OUTSIDE_FOR = "" +

"function countMethodPropAllocOutsideFor(n) { " +

" var ret = 0; " +

" const adder = new Adder(); " +

" for (let i = 0; i < n; i = i + 1) { " +

" ret = adder.add(ret, 1); " +

" } " +

" return ret; " +

"}";

@Override

public void setup() {

// ...

this.truffleContext.eval("ezs", COUNT_METHOD_PROP_ALLOC_OUTSIDE_FOR);

this.truffleContext.eval("js", COUNT_METHOD_PROP_ALLOC_OUTSIDE_FOR);

}

@Benchmark

public int count_method_prop_alloc_outside_for_ezs() {

return this.truffleContext.eval("ezs", "countMethodPropAllocOutsideFor(" + INPUT + ");").asInt();

}

@Benchmark

public int count_method_prop_alloc_outside_for_js() {

return this.truffleContext.eval("js", "countMethodPropAllocOutsideFor(" + INPUT + ");").asInt();

}

}

Let’s see what’s the performance difference between them:

Benchmark Mode Cnt Score Error Units

InstanceMethodBenchmark.count_method_prop_alloc_inside_for_ezs avgt 5 295.620 ± 10.630 us/op

InstanceMethodBenchmark.count_method_prop_alloc_inside_for_js avgt 5 293.406 ± 3.974 us/op

InstanceMethodBenchmark.count_method_prop_alloc_outside_for_ezs avgt 5 294.061 ± 4.078 us/op

InstanceMethodBenchmark.count_method_prop_alloc_outside_for_js avgt 5 296.810 ± 2.346 us/op

As it turns out, the performance is identical in both cases!

This means Graal was clever enough to inline the call to the add() method,

and completely eliminate the allocation of any instances of the Adder class.

Summary

So, those are the basics of implementing class support in Truffle languages.

As usual, all code from the article is available on GitHub.

In the next part of the series,

we will allow storing state in our classes by adding support for fields,

the this keyword, and constructors.

This article is part of a tutorial on GraalVM's Truffle language implementation framework.

- Part 0 – what is Truffle

- Part 1 – setup, Nodes, CallTarget

- Part 2 – introduction to specializations

- Part 3 – specializations with Truffle DSL, TypeSystem

- Part 4 – parsing, and the TruffleLanguage class

- Part 5 – global variables

- Part 6 – static function calls

- Part 7 – function definitions

- Part 8 – conditionals, loops, control flow

- Part 9 – performance benchmarking

- Part 10 – arrays, read-only properties

- Part 11 – strings, static method calls

- Part 12 – classes 1: methods, new

- Part 13 – classes 2: fields, this, constructors

- Part 14 – classes 3: inheritance, super

- Part 15 – exceptions

- Part 16 – debuggers