Unit, acceptance or functional? Demystifying the test types – Part 3

This is Part 3 of a 4-part article series about the different types of tests.

Integration tests

Integration tests are interesting, because I believe they are as misunderstood as unit tests – however, the reason for that misunderstanding is the exact opposite of the reason for unit tests. While unit tests suffer from being under defined, integration tests are defined too well.

If you ask almost any programmer what are integration tests, he will almost invariably answer with some variant of the following: “Integration tests work by combining the units of code and testing that the resulting combination functions correctly”.

That definition never made any sense to me. It’s somehow implying that it’s not enough to test calling myClass.someMethod() in unit tests – that I have to do it again, just this time together with other components, because for some reason, it might stop working then. Very weird, in my opinion.

However, I really think that the concept of integration tests is not hard, and the easiest way to explain what they are is to contrast them with unit tests.

If the defining trait of unit tests is isolation, then for integration tests it would be deliberately giving up isolation. The entire point of integration testing is to take those messy parts that we abstracted and mocked away in unit tests, bring them to light, and exercise them in a test harness to see if they work as intended.

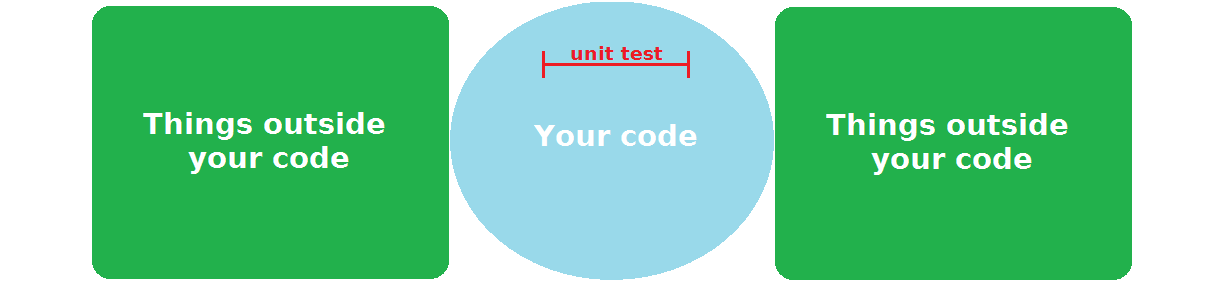

Maybe the easiest way to illustrate what I mean is with some diagrams. If we imagine our project as consisting of things we control (our code), and things we interact with, but don’t control (“the outside world”), a unit test would look something like this on that diagram:

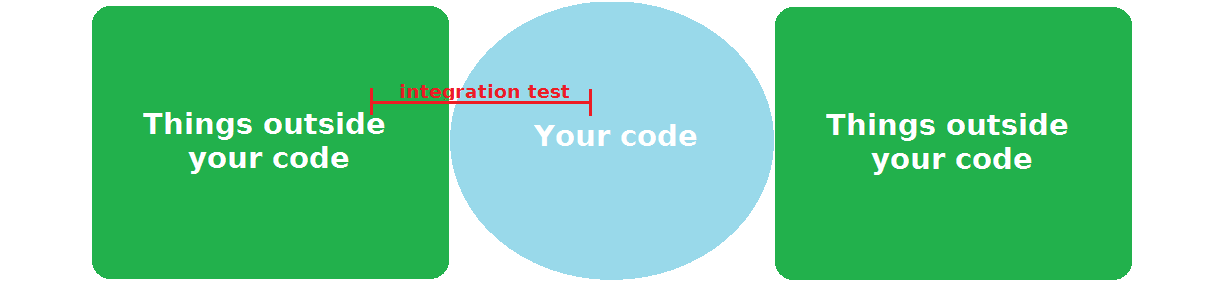

It’s concerned only with your code, each exercising a part of it, obviously. Now, an integration test, for contrast, would look something like this:

An integration test selects some aspect from the “things outside of your control” area, and then exercises your code that is meant to interact with it – using an authentic instance of that “thing”, not some fake one like a unit test would – to verify that the code is in fact correct.

Note that “correct” in this case is always judged from the outside thing’s perspective. As that is something you don’t control, you cannot simply conclude that that thing is wrong, and your code is right. If the integration fails, then the application will not work, and it’s your responsibility to fix that. Even if you are 100% certain that the outside thing’s behavior is a bug, you have to work around it (this tends to happen fairly frequently, for example, when your application needs to integrate with some large, expensive, closed-source shrink-wrapped software product).

Of course, this means that you need to take this external thing, and make sure that a) it’s available to be used in a testing context, and b) it satisfies the pre-conditions of the test that you are about to run. This is the part that makes integration tests so much more trickier to write and run than unit tests.

What exactly is “the outside world”?

We have used this vague notion of “the outside world” (calling it also “things outside of your code/control”) several times in this article already. Like I promised earlier, I would like to define it more precisely, as I think it’s quite a crucial issue to understand.

When I say “the outside world”, what I mean by that are all of the entities in the system that are essential to it’s correct functioning, but which are not a product of your code. Now, that definition might sound weird and abstract, so let me give a few examples of those “external things” commonly seen in real-world projects.

- Databases

-

A database is always external, always independent of your code, and absolutely essential to the correct functioning of your system. And it doesn’t matter whether your project is using a boring, old relational database like MySQL, or the newest hipster NoSQL graph storage. Databases are big, complex software with many intricacies and corner-cases, and you absolutely need to get interacting with them right.

I remember working on a project where I was responsible for a piece of functionality that would store some data in PostgreSQL. I developed a very elegant class model in Java for the problem, using inheritance, and I had great test coverage for my code using an in-memory database. I was super confident that everything would work perfectly from the get-go. I deployed the application to the test environment that used PostgreSQL… and everything blew up.

Turns out, there was a bug in the version of the JDBC PostgreSQL driver I was using, that caused Hibernate to blow up when simultaneously using

@DiscriminatorColumn(discriminatorType=INTEGER)and@GeneratedValue(strategy=IDENTITY). Yeah, seriously. I changed the code to use@GeneratedValue(strategy=AUTO), and everything worked as expected.In this sort of situation, it doesn’t matter how beautiful the code you’ve written is, or if you have even 100% unit test coverage. Unless you perform an integration test against the same database that your system is using, you cannot ever be certain that your code will actually work.

(On a different note, this is also a great example of working around the bugs of the software you are integrating with that I mentioned earlier)

- External services

-

This is probably the most common understanding of the term ‘integration’ – talking to some external system through a well-defined API. There is a lot that can go wrong with this sort of setup – the smallest misconfiguration, and the two sides will be unable to understand each other. Anyone who tried to change the signature of a Java remote EJB method call will surely agree with me. Another example would be the secret tokens that a lot of APIs generate for you in order to authenticate. You usually have to perform some cryptographic operations using the given key to sign the request in a specific way. You can never be 100% certain you’ve done it correctly until you call the API and get a positive answer back. For these kind of concerns, unit tests are pretty much useless.

Note that in our modern era of microservices, this sort of communication pattern is much more common, and not restricted only to the boundary of your system – on the contrary, the majority of your internal components will most likely talk to each other this way. Which means properly testing these interactions – using real clients and servers, not mocks – becomes even more crucial.

- Frameworks/libraries

-

These probably aren’t the first things that come to mind when thinking about integration tests. However, it’s very important to realize that there are as outside of your control as a database or an external system.

Frameworks and libraries often place restrictions on your code, and will break if you don’t follow them perfectly. A simple example in the Java world might be JPA (the Java Persistence API) – the ORM (Object-Relational Mapping) solution. The

@Entityclasses that map to the database tables must fulfill certain criteria for it to work correctly. So, it doesn’t matter how well you have unit tested your entity class – if you forgot to declare a no-argument constructor for it, or declared the classfinal, the code will break as soon as you try to talk to a database.An often tricky part of working with some frameworks and libraries is that a lot of them have not been designed with easy testability in mind, which means asserting the correctness of your code from their perspective is very hard to do in a test. Java Enterprise Edition is notorious for this (try writing a test checking if you are using JNDI correctly, and you’ll see what I mean).

Unit vs. integration – an example

Finally, I want to show how does the approach vary between unit and integration tests on a concrete example. We will be using the following Spring controller:

@RestController

@RequestMapping("/api/")

public class UserController {

private final UserRepository userRepository;

@Autowired

public UserController(UserRepository userRepository) {

this.userRepository = userRepository;

}

@RequestMapping(value = "/users", method = RequestMethod.GET)

public List<User> get() {

return userRepository.users();

}

}

User is a simple value class with email and age fields:

public final class User {

private final String email;

private final int age;

public User(String email, int age) {

this.email = email;

this.age = age;

}

public String getEmail() {

return email;

}

public int getAge() {

return age;

}

}

Now, we could write a simple unit test for this Controller – like this:

public class UserControllerUnitTest {

private UserRepository userRepository;

private UserController userController;

@Before

public void setUp() {

userRepository = mock(UserRepository.class);

userController = new UserController(userRepository);

}

@Test

public void get_returns_users_from_repository() {

when(userRepository.users()).thenReturn(asList(

new User("unit1@test.com", 30),

new User("unit2@test.com", 40)

));

List<User> users = userController.get();

assertThat(users)

.extracting("email", "age")

.containsExactly(

tuple("unit1@test.com", 30),

tuple("unit2@test.com", 40));

}

}

And while this test is fine, I don’t think it adds too much value.

- It doesn’t actually test the Controller aspect of the class. We can remove the

@Controllerannotation, and it would still pass. - The paths for the endpoint are untested. For example, we used

/api/on the class, and/userson the method – will Spring handle it correctly, and it will be available at/api/users? (spoiler alert – yes, it works like that) - Our Controller is supposed to return JSON data, however that aspect of the code is completely unverified.

Fortunately, Spring is a technology that has always put testability as one of its primary goals. Because of that, it’s fairly easy to write an integration test verifying all of those things that the unit test was unable to check:

@RunWith(SpringJUnit4ClassRunner.class)

@SpringApplicationConfiguration(classes = TestSpringConfiguration.class)

@WebAppConfiguration

public class UserControllerIntegrationTest {

@Autowired

private WebApplicationContext wac;

@Autowired

private UserRepository userRepository;

private MockMvc mockMvc;

@Before

public void setUp() {

mockMvc = MockMvcBuilders.webAppContextSetup(wac).build();

}

@Test

public void get_returns_users_json() throws Exception {

when(userRepository.users()).thenReturn(asList(

new User("integration1@test.com", 33),

new User("integration2@test.com", 44)));

mockMvc.perform(MockMvcRequestBuilders.get("/api/users"))

.andExpect(MockMvcResultMatchers.status().isOk())

.andExpect(MockMvcResultMatchers.content().json(

"[" +

"{" +

"\"email\": \"integration1@test.com\"," +

"\"age\": 33" +

"}," +

"{" +

"\"email\": \"integration2@test.com\"," +

"\"age\": 44" +

"}" +

"]"

));

}

}

Here is the TestSpringConfiguration class (the Application is the production configuration):

@Configuration

@Import(Application.class)

public class TestSpringConfiguration {

@Bean

public UserRepository userRepository() {

return Mockito.mock(UserRepository.class);

}

}

As you can see, we are using the MockMvc class that allows you to simulate standing up the application and sending it requests. Now, all of those aspects that were untouched by the unit test are verified.

You might be surprised that we are still using a Test Double for the UserRepository in this test. Wouldn’t using the real one here make sense?

In my opinion, the test is better this way. Ideally, in each integration test, we are focused on verifying only some aspects of our code dealing with “the outside world” (ideally just one, but that’s often difficult to achieve in practice). This way, the tests are faster, more isolated and easier to write. For example, if we were to use a real UserRepository instead of a Stub here, we would a) make the test more fragile (it would fail if the database was down, for instance, while this one wouldn’t), and b) it would be considerably longer and more complex (the setup would have to initiate the database, and then clear it afterwards).

I think a much nicer solution is to have separate integration tests verifying the behavior of the UserRepository, using a real database, in isolation from the rest of the application. This way, you can be much more thorough in your repository tests, making sure all of the intricacies and corner cases are adequately handled, without worrying about how to cause those unlikely scenarios through the entire application stack, which is predominantly concerned with the “happy-path” case.

As you can see, integration tests, while valuable, might still leave some facets of the application not verified. And this is where our last type of tests enter the picture.

This is Part 3 of a 4-part article series about the different types of tests.