My primer on Docker

Docker seems to be the cool new thing right now. It feels like you can’t visit HackerNews or /r/Programming without stumbling upon some news item or blog post about it. The one thing that I haven’t seen, however, is a good introduction to the topic for people completely new to the subject. It seems like most introductory articles focus almost exclusively on the ‘how’ – that is, Linux containers – forgetting the more important questions for beginners: the ‘what’ and the ‘why’.

I’ve recently been to a Warsjaw JUG meetup on the topic, and I think I know enough now to try and rectify this situation. So, here’s my attempt at an explanation of Docker for absolute beginners.

The ‘what’

So, the first question is ‘what’. What the hell _is_ Docker? This seems like a pretty obvious thing to ask, but surprisingly the answers are anything but obvious. For example, Docker’s official page defines it as ‘an open platform for developers and sysadmins to build, ship, and run distributed applications’. I don’t know about you, but to me that means absolutely nothing. To aid understanding and lay the foundation for the rest of the article, I would like to propose the following definition:

Docker is a tool to create, run and manage lightweight virtual machines – called containers.

While experts in the matter may frown at this, I think it’s close enough to the truth, and should give you some instant intuition about what all the fuss is about. The ‘distributed applications’ mentioned above – they live in those lightweight VMs, and because they do, they can be distributed (because the VMs can).

The second question is ‘why’. Why is something like Docker needed at all? After all, virtualization technology has been around for decades. Why can’t we use that? Well, the key to understanding those reasons are two words used above – ‘lightweight’ and ‘distributed’. But in order to get to that, we need to take a look at the way traditional virtualization works.

Traditional Virtual Machine architecture

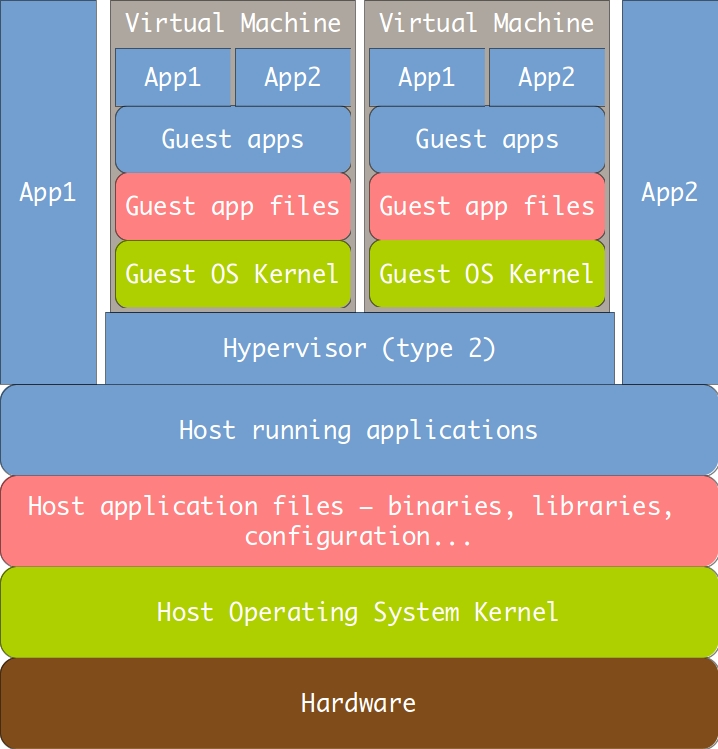

Since it seems that every article on Docker at this point is legally obligated to include at least one confusing diagram illustrating how it works, here’s mine:

This is a sketch of how a traditional virtual machine works. We have all the host layers, and the guest lives inside a process on the host. The guest includes all of the same layers the host does – its own copy of an entire operating system and its own runtime for the applications running in it. This allows maximum isolation between the host and the guest and between multiple guests. This is a fine design – nothing wrong with it. I use it myself – I’m writing this article in a VirtualBox-hypervisored guest running Ubuntu Desktop, which itself runs in a Windows 7 host, exactly like shown above. This design, however, has some very concrete repercussions:

- Performance overhead. As can be seen in the diagram, applications running in the guest have quite a few layers of abstraction beneath them. The biggest one is the hypervisor, which provides a kind of virtual hardware that the guest OS kernel interacts with. This allows the same, unmodified operating system to be used both as a host and a guest. The trouble is, of course, that it makes that OS significantly slower when ran as a guest. There is some modern technology that allows the guest to subvert the hypervisor and talk with the hardware directly (like VT-x or Nested Pages), but the fundamental issue remains.

- Memory overhead. Modern operating systems have quite a large memory footprint – at least in the order of hundreds of megabytes, often in the gigabytes. Each running virtual machine will use at least that amount of memory, and that’s even before you account for the memory used by the application(s) running inside it.

- Size. Because the guest has to include its own copy of an operating system, it means that it requires a large amount of disk space – in the range of tenths of gigabytes. This makes distributing virtual machines cumbersome for a small number of targets and downright impossible for a large number of them. There are tools (like Vagrant) that try to mitigate this issue by allowing describing a VM state in a programmable DSL text format, from which the VM is provisioned on demand on a particular host. This provisioning, however, has its own downsides:

- because it uses regular OS update mechanisms (like the

aptpackage manager for Debian-family guests), it requires an Internet connection on all hosts - downloading all of the needed files can take a significant amount of time – usually in the order of minutes

- the biggest flaw: this provisioning usually doesn’t freeze the versions of the packages used. Which means that it doesn’t actually guarantee uniformity between different hosts, as one that was provisioned later might have newer versions of the needed packages, which may conflict with older ones installed on other hosts. This makes the entire process non-deterministic and not repeatable

- because it uses regular OS update mechanisms (like the

- Startup overhead. The guest operating system has to boot. Then it has to initialize all of the applications it uses. This, because of point #1, can take quite a significant time. Modern virtualization tools allow you to suspend machines – which is analogous to hibernating your laptop instead of shutting it down – but resuming a suspended machine still takes time in the order of seconds, which is quite a while in computer-land, and does nothing to quicken the first boot.

All of the points above suggest that traditional VMs have very specific use cases – similar to the one I described above, that I use personally. Its characteristics can be described as: needing isolation between your host and guest(s), needing all the functionality that a modern operating system provides in your guest, running on a host with lots of memory, and most likely running a large number of independent applications in your guest simultaneously – but at the same time not running a large number of separate virtual machines on a single host. For use cases matching these criteria, traditional virtualization is a great fit, and the advent of Docker does not change that.

The ‘why’

And this is where we get to the ‘why’. Because, in this modern era of the Cloud, web-scaling, various IaaS, SaaS and PaaS providers and microservices, there is another use case for which all the above points are deal breakers. That use case is running a single application on a possibly large Cloud cluster of hosts. Its characteristics are basically opposites of the above. We don’t really care about isolation – the host is most likely a virtual machine itself, so it’s already isolated. We also don’t care about nothing else in the guest except that one application that we want to run – the only things that matter is that application and its dependencies, everything else is dead weight.

Suddenly, because Cloud machines are themselves VMs, the overhead from a traditional hypervisor may be too great to ignore. These VMs are usually memory constrained – and adding more memory usually means higher annual costs. Those same costs may also encourage running multiple containers on a single host. Because we want flexible scaling on potentially hundreds of nodes, there is no way we can incur the startup penalty of booting a separate operating system and then waiting for it to provision. At the same time, because all we are interested in is running a single application, dragging around tenths of gigabytes of files that we will never use is nonsensical.

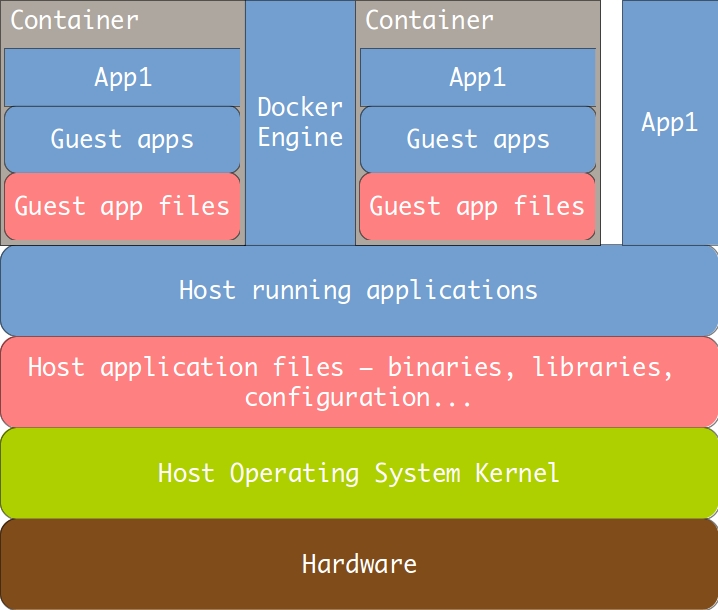

And this is where Docker enters the picture. Below is a diagram of how a Docker container works.

Docker containers solve all the problems outlined above. They talk with the host OS kernel directly, so there is practically no overhead. They don’t have an entire operating system embedded inside them, so they are small – in the range of hundreds of megabytes. That is small enough to allow them to be distributed, in their entirety, through modern Internet connections. There is no booting penalty. There is also no provisioning – because of the small size, containers are provisioned in advance, and only then distributed. This means that every container can be exactly the same, on the file byte level, as every other one in a cluster. This allows us to achieve perfect uniformity and repeatability of our environments.

With a solution like that in place, a whole new world of opportunity opens up. You can imagine other scenarios that were simply not feasible with traditional virtual machines. For example, let’s say you’re building a web application. The production setup consists of three servers – an application server holding your application, a database server that is used for storage, and a web server like Apache or Ngnix for handling stuff like caching and serving static assets. You want to create an automated local environment so that new developers don’t have to waste time setting everything up and so you have a reliable way to test the application before rolling it out. Naturally, you want that local environment to resemble the production architecture as much as possible. With VMs, you would probably cram all that applications into one guest, to make maintenance easier and reduce overhead. That would be fine, but it wouldn’t be that reliable – this setup isn’t that close to the production one. And what if you needed to scale production, and add another application server and make the web one act as a load balancer? With Docker, this is all trivial. You set up three containers, each with its own application, and that’s it. This model can be seamlessly scaled with time as your application matures and scales itself. I hope you can see that the possibilities here are truly endless.

The ‘how’

Now that we know the ‘what’ and the ‘why’, it’s finally time to talk about the ‘how’. How is Docker able to achieve those levels of performance and size? It’s all possible thanks to something I mentioned already – Linux containers. This is a way in Linux to completely isolate a group of processes (through various means that I won’t go into detail about, because it’s not that important) from the rest of the system. That group will have its own PID namespace, its own users and privileges, even its own view of the filesystem. Processes in a group like that will have no knowledge of anything in the system outside of that group except for what you explicitly grant it access to. In that sense, a container is very similar to a virtual machine. The fundamental difference is that this design deliberately gives up some isolation that a traditional VM offers. The most basic limitation is that the host and the guest must use the same operating system – so you can’t replicate my setup with a Windows host and a Linux guest that I mentioned above. Another thing is that processes outside containers can see the ones inside them – so the isolation is “one way”. Finally, an important fact is that the name “Linux containers” is not a coincidence – the means by which a process group is isolated are native to the Linux kernel and outside the scope of any standard like POSIX. Which means Docker can only be natively (there are some workarounds, usually involving – ironically – a virtual machine) ran on a Linux host – you can’t do it with Windows, OS-X or BSD (although Microsoft recently announced that containers API support will be coming to Windows in the near future, so who knows – expect rapid changes in this space).

I mentioned above that a container will only have access to what you explicitly put inside it. And this is where Docker comes in. It defines a format of something called an image. An image is similar to a commit in Git – it is a snapshot of a state of a file system. Those images are then used to create containers. As you can guess, the container will see those filesystem contents when it runs – this is a way to give containers access to those applications they are supposed to host. Docker provides you with these so called base images – things like an image including all binaries for programs present in the newest Ubuntu Desktop release. When you have that, you can then provision that container with, let’s say, an Apache package from apt, and bam – you have your own personal, small virtual machine capable of running whatever version of Apache you please. This provisioning creates a new image from the base one. This creation is done very efficiently – only the delta needed to go from the old image to the new one is saved, which takes less space (which is important when downloading images – you only need to download the small delta if you already happen to have the base image). Any image consists of a base image and a series of deltas. This is another way in which it is similar to a commit in Git – you can think of the deltas as the history of the image. You can then distribute that imagine across servers, or put it inside a repository to be shared between members of your team. You can even publish it on DockerHub – an online repo which makes images available publicly for everybody to download and use (DockerHub is the place you get the base images from).

I hope this overview is enough to give you an idea of how Docker works. If you want to find out more, I recommend you head to Docker’s official userguide.

Summary

Docker is a cool technology, but I know I personally had trouble grasping exactly how it worked from the materials I could find online. I hope this article was helpful in bringing its ideas closer to home and showing how it can be useful.